Dicamba Poses Tough Questions, Few Answers For Farmers, Regulators

Farmers in Indiana and across the nation are using more of a powerful, but controversial, weed killer this year — dicamba.

Dicamba has been used since at least the 1960s, mostly on corn. Last year, though, the Environmental Protection Agency approved a new type of dicamba to use on cotton and soybean plants genetically engineered to resist the weed killer.

Don Lamb, who operates an 8,800 acre farm in Lebanon, says the new dicamba has created a problem.

“The part’s that new is the fact that you could be spraying a soybean and the field next you looks very similar to what you have but it’s not because the genetics of that soybean are different,” Lamb says.

Dicamba kills soybeans not engineered to tolerate it. And farmers across the country say the new formulation drifts very easily. Lamb says farmers are used to dealing with drifting herbicides, but this year, it’s much worse.

In Indiana alone, there’s been 121 dicamba related drift complaints since the end of August. Millions of acres have been damaged nationwide.

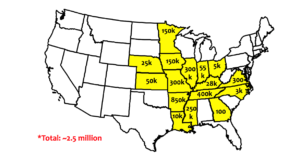

Estimates in acres of soybeans injured by dicamba from state university scientists as of July 19. Researchers believe the true number could be over 3 million acres. (Courtesy Kevin Bradley/University of Missouri)

Still, while the product is tricky to use, there is a need for it. Weeds are increasingly resistant to glyphosate, a weed killer more commonly known as Round Up.

“That is an example of a weed that is resistant to glyphosate,” says Lamb, pointing to a weed standing tall above his knee-high soybeans. Those were sprayed at a time when they should’ve died. And they didn’t.

Companies producing these new soybeans, such as Monsanto and DuPont, say if farmers follow the directions on the dicamba label, there’s no problem with drift. But Lamb says it’s not that simple. The label is actually a small book, and there’s a website on top of that.

“That’s my responsibility as a farmer, as an applicator,” Lamb says. “I need to do what the label says. And if the label’s too restrictive, don’t use the product.”

Don Lamb’s brother, Dean, modifies a new piece of equipment. “A lot of times you buy a new piece of equipment and you think it’d be ready to go, but farmers all do things differently,” says Don Lamb. (Nick Janzen/IPB News)

Another way to reduce risk, says Steve Smith, director of agriculture for tomato processor Red Gold, is education.

“It was surprising,” says Smith. “For us to have not had any issues, I feel really good about that people worked hard to try to prevent problems.”

Tomatoes are also highly susceptible to dicamba damage, and with Red Gold’s crop worth 10,000 dollars per acre, the company was sure to work with its neighbors.

But Smith says education may not be enough.

“I think the science of the matter is pointing very clearly to the fact that … the atmospheric conditions and the characteristics of the chemistry itself are going to mean that a certain percentage of the time the conditions are going to be just right for it to move where it’s not supposed to go,” Smith says.

Indiana’s Pesticide Review Board regulates weeds killers. Prior to this year’s growing season, it hoped there wouldn’t be a need for tighter dicamba rules at all. But Dave Scott, pesticide administrator for the Office of the State Chemist, says it hasn’t turned that way. His office has received an unusually high number of complaints this year. And it takes months of field and lab work to determine if dicamba was involved in one.

“If we found out everybody’s sloppy and didn’t follow the label, then there’s a chance to fix that by cracking down on the applicator,” Scott says. “If it’s a situation, like, everybody did everything legally but bad stuff still happened, then you have to look at do there need to be more restrictions on the use that would prevent the bad stuff from happening.”

Indiana regulators could require applicators to keep more detailed records about how they use the weed killer. And the EPA recently announced it’s considering a cut off date for dicamba use next growing season, something Red Gold advocates for Monsanto, though, has said that isn’t necessary.