Report: Livestock Farms Good For Economy Despite Opposition

The animal agriculture industry in Indiana is growing faster than the nation as a whole in most categories. A recent report from the Indiana Soybean Alliance says that’s good news for Indiana’s economy. But as Indiana Public Broadcasting’s Becca Costello reports, some Hoosiers say the consequences outweigh the benefits.

Andy Tauer operates a small farm in west-central Indiana.

“My wife and I actually built our house here on the farm eight years ago, but really this farm has been a part of my family since the late 1800s,” Tauer says.

That red farm house with a large front porch is surrounded by fields of corn, soybeans and pastures for a few dozen cows.

“All of our cows have names. This cow is Chocolate,” Tauer says, patting the sow on the back. “Actually, we bought that cow for our oldest daughter and then when we sell her babies that money goes into a college fund for her. And then the red cow, which is Lucy, is our youngest daughter’s and we do the same thing on those.”

Tauer is also the Director of Livestock at the Indiana Soybean Alliance.

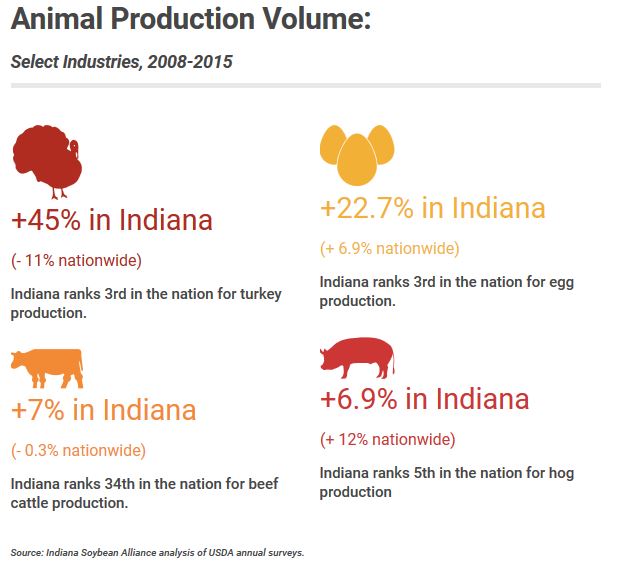

The organization worked with the Indiana Business Research Center this year on a report that determined Indiana is outpacing the nation’s animal agriculture growth in every major category.

For example, turkey production declined 11 percent in the U.S., but increased 45 percent in Indiana between 2008 and 2015.

Indiana is among the nation’s top producers of turkeys, hogs, and eggs.

But Tauer says the most important finding of the report is that this growth isn’t just good for farmers.

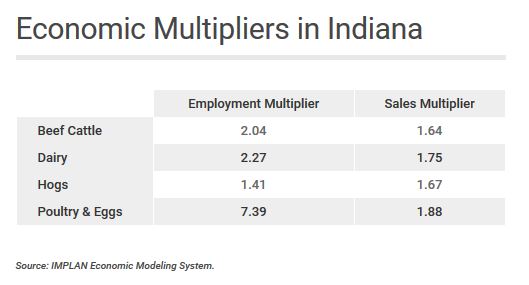

“The impact on the entire state economy is pretty large. Because you start to figure in not just the increase in economic activity at the individual farm level, but that creates opportunities in the trucking industry, the feed industry, all the different service industries,” he says. “So it really creates this ‘ag-effect’ across the state that really kind of brings the entire economy up.”

In the report, this ‘ag-effect’ is called a multiplier effect. It means that a livestock operation has an impact on both employment and sales. For example, an employment multiplier of 1.41 means that every employee working in the industry supports another 0.41 jobs in other industries. And a sales multiplier of 1.67 means that every dollar of sales for a livestock producer generates another $0.67 in sales for other business in Indiana.

Purdue University agricultural economist Chris Hurt says a relatively small livestock operation indirectly boosts all aspects of the local economy.

Purdue University agricultural economist Chris Hurt says a relatively small livestock operation indirectly boosts all aspects of the local economy.

“Agriculture is something that we can use to generate more economic development. And there’s a reason to focus on agriculture because we have the natural resource base right here,” Hurt says. “Everyone wants to be the next Silicon Valley, but why would Indiana be the next Silicon Valley?”

Hurt says this kind of growth is ideal for Indiana – because it’s bringing jobs to places where there aren’t many other options.

“The large-scale animal operation has economic benefits,” Hurt says. “It creates opportunities in economic development and employment, in rural areas where it’s really hard to attract the next major employer to come into that community.”

CFOs & CAFOs

But when we talk about livestock operations, we’re usually not talking about Tauer’s idyllic farm with less than 20 cows.

Instead, the Soybean Alliance report refers primarily to Confined Feeding Operations, or CFOs – these are farms with a large number of animals in one place. Indiana has close to 2,000 CFOs.

Operations with a higher number of animals are called Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations, or CAFOs.

Both are regulated by the Indiana Department of Environmental Management, which enforces regulations about what farms do with all that manure, how close they can be to water sources, public roads and more.

But for some Hoosiers who live next to a CFO or CAFO, it’s not enough regulation.

“Oh my gosh. It hit with a vengeance,” says Nancy Banta, referring to the smell produced by a nearby CAFO.

Banta lives near a CAFO in Bartholomew County in a small town called Hope. Earlier this year, Banta and other homeowners successfully lobbied the county to charge them less in property taxes because the value of their homes is decreased by the CAFO.

“My quality of life, I had to rethink everything about it,” she says. “I can no longer have my grandchildren over here to play because of that.”

As for an economic boost? Banta says the CAFOs aren’t bringing jobs to an economically depressed area – instead, they’re taking advantage of a vulnerable community.

“It truly is all about economics, it truly is there is no money here. We are the poorest township in Bartholomew County. That essentially … is why they’re here,” Banta says. “Because they’re not going to be able to push back in any way, they don’t have the means to push back, they don’t have the representation in any kind of county government that’s going to look out for them. They’re an easy target.”

Changing Public Perception

Chris Hurt says Hoosiers tend to look at large livestock operations with uncertainty and suspicion.

“The uncertainty we work on with education, with visitation, with showing people that these are good environmental stewards. And then the suspicion tends to fade away and we say, ‘this is an acceptable means of operation,’” Hurt says. “Nothing is all good or all bad. Look at the good, look at the bad but recognize that there are positives out of these operations and that we need to learn more about them.”

Tauer echoes that sentiment but adds it’s difficult to give people a first-hand look because letting people see the big operations in person risks exposing the animals to disease.

But, Tauer says, the farmers running CFOs or CAFOs are mostly Hoosiers who’ve farmed here for generations.

“I think at the end of the day, what’s really important for us at the Indiana Soybean Alliance is just that folks understand that these farm families that are expanding into animal agriculture, they’re invested right there in the community along with the neighbors,” Tauer says. “So they’re not going to do something that’s going to be detrimental to them that would also be detrimental to the community.”

Tauer hopes the Indiana Soybean Alliance report will help put people at ease about livestock farming.

State lawmakers are considering regulations for CAFOs in a summer study committee. A bill to streamline the permitting process for CAFOs died in the Senate this year.