Less ice on Lake Michigan means more shoreline damage and warming, but also more snow

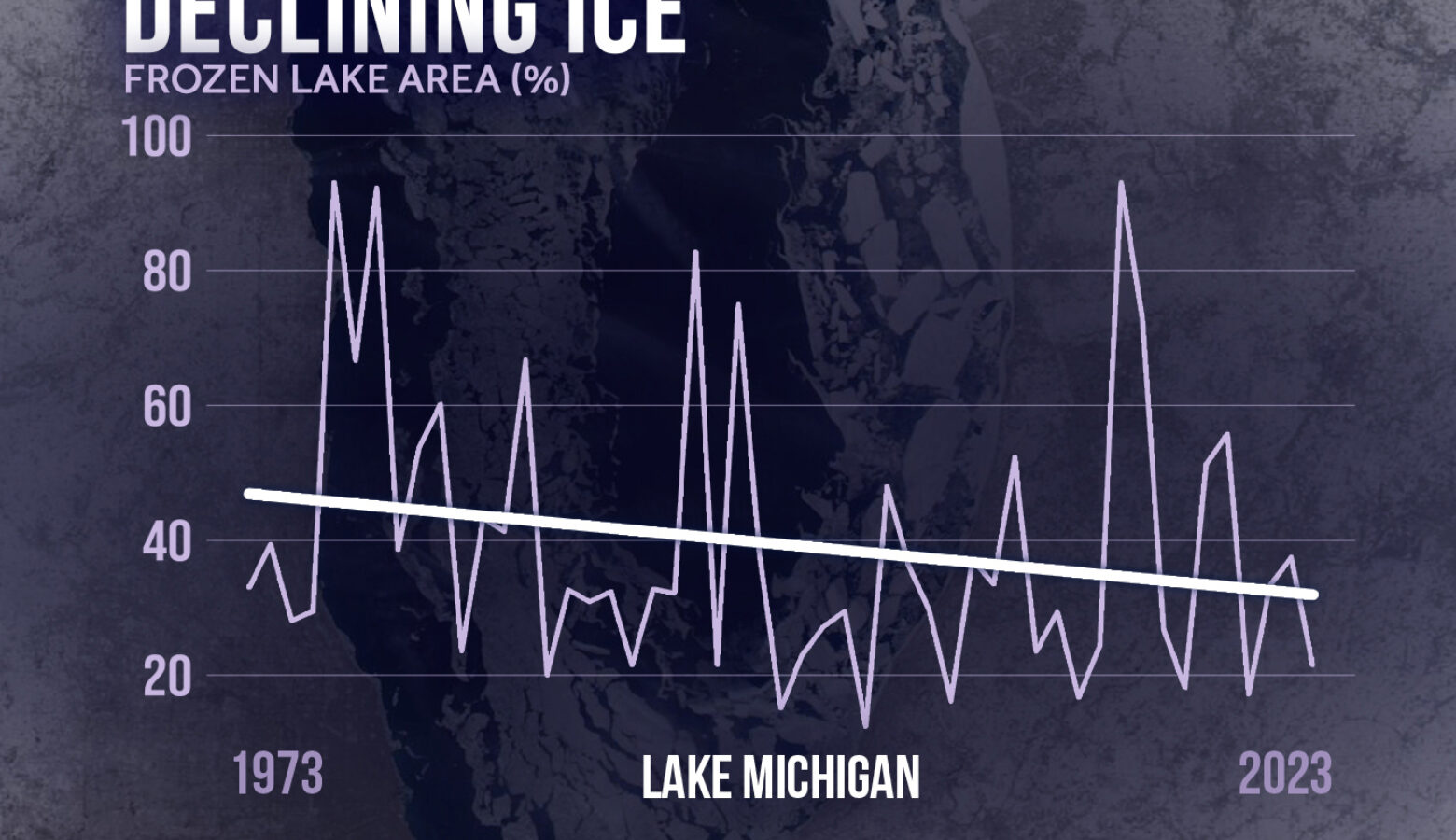

Lake Michigan and the rest of the Great Lakes haven’t had much ice this winter. According to the independent research and reporting collaboration Climate Central, Lake Michigan is frozen for 22 fewer days now than it was in the 1970s and ice cover is less than what it used to be.

Melissa Widhalm is a climatologist and associate director at the Midwestern Regional Climate Center at Purdue University. She said the melting lake ice is part of the reason why we see winters in the Great Lakes region warming faster than in other parts of the country.

“It creates a feedback loop, right, where you have warmer temperatures that take away some of that snow and ice, which causes less sunshine to be reflected, which helps you warm up even more, which further melts that snow and ice and the cycle kind of continues,” Widhalm said.

Less ice also puts more moisture from the lake into the atmosphere, leading to more lake effect snow like what northwest Indiana experienced in mid-January.

READ MORE: Have trouble understanding climate trends in Indiana? A climatologist gives their tips

Join the conversation and sign up for the Indiana Two-Way. Text “Indiana” to 765-275-1120. Your comments and questions in response to our weekly text help us find the answers you need on climate solutions and climate change at ipbs.org/climatequestions.

Though less ice means more shipping can take place on the lakes, it spells bad news for Indiana’s lakeshore towns.

That ice serves as a barrier — preventing big winter waves from crashing against the beach, eroding roads and infrastructure for homes. In 2019 and 2020, the erosion was so damaging that lakeshore towns were in a state of emergency.

Donna Norkus is on the town council for Beverly Shores. She said though the town hasn’t seen as many storms this winter, erosion is an ongoing problem.

Beverly Shores is working with other cities along the Great Lakes to look for long-term solutions and the money to pay for them.

“The solutions that have been proposed are in the several, several, several multi-million range which a town of 500 homes can’t afford,” Norkus said.

That includes removing hard barriers that block the flow of sand in some areas while putting up boulders to calm waves in others. Some areas might benefit from “pocket beaches” where the sand on either side juts out into the lake.

Rebecca is our energy and environment reporter. Contact her at [email protected] or follow her on Twitter at @beckythiele.