Sundown Towns in Indiana: How a Legacy of ‘Whites-Only’ Towns Rose and Continues to Affect Today

In reporting and presenting a story on historic practices of racism, language and images that are offensive are included in this report. Reader discretion is advised.

When the state of Indiana was founded, the original 1851 state constitution barred people of color from settling in the state, a move that was overturned or repealed by the Supreme Court during Reconstruction following the Civil War.

After slavery was abolished and African Americans began to move from the places they’d been forced to live in, white communities began to revolt. They ran Black people out of their cities or counties, under threat of violence or death, and enacted laws to keep them out.

These communities, known as Sundown Towns, arose in the early to mid 1900s, and their effects continue in many towns today.

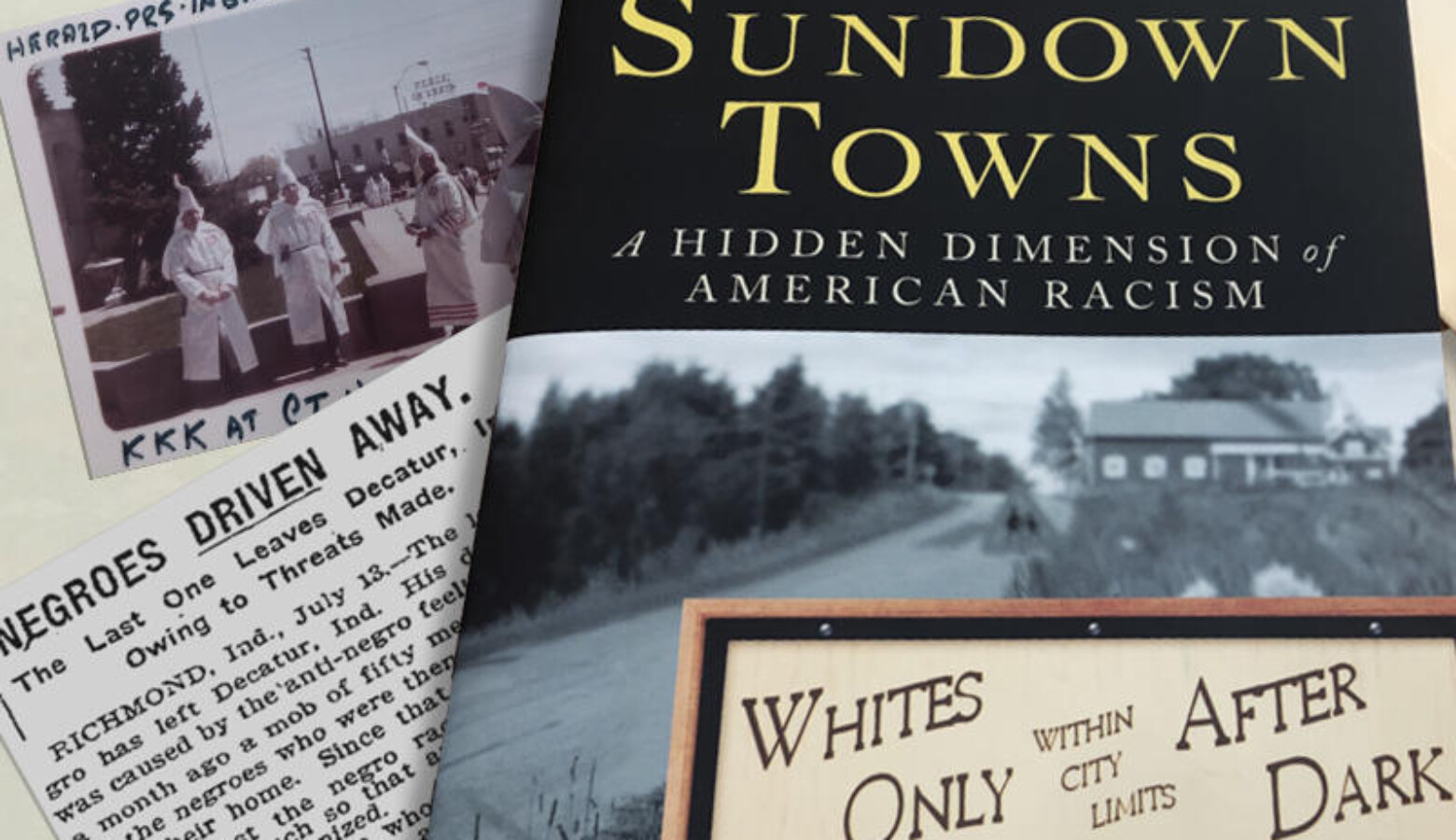

James Loewen is the author of ‘Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism’. Loewen has spent years researching and trying to catalogue towns that historically kept Black people out of them – by whatever means necessary.

“Sundown Towns are towns that were for decades all white on purpose, and some of them still are. It turns out that they’re all across the midwest.”

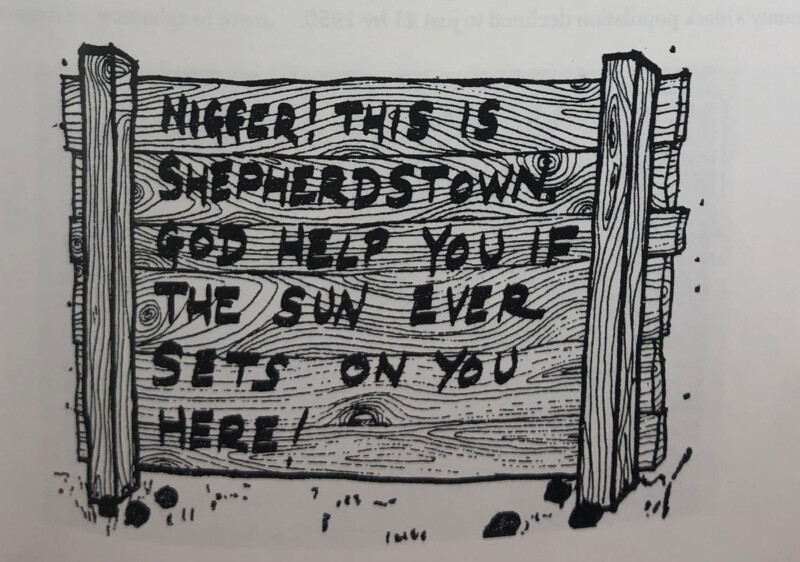

Some towns had signs that made their intentions clear. One that says ‘Whites only within city limits after dark’ covers the front of Loewen’s book. Others used more crass language, racial slurs or threats of violence to get their point across.

“They’re in Oregon, they’re in California, they’re in the far west. They’re in Pennsylvania. They’re almost everywhere except the traditional south.”

Sundown Towns weren’t typically a Southern thing, Loewen said. Because, in the South, white people wanted Black people in their towns to do the jobs they didn’t want to do – janitors, maids, cotton pickers.

“But, across the Midwest it turns out, all kinds of towns – hundreds of them in Indiana, even more hundreds in Illinois.”

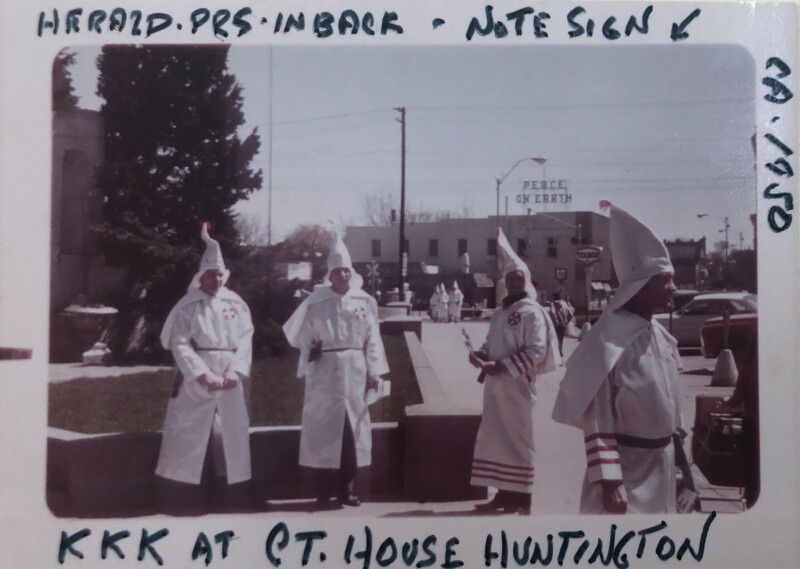

Between the 1890s and the 1940s, Sundown Towns became a popular trend in Northern states. In his book, Loewen profiles three Indiana towns; Elwood, Huntington and Martinsville.

John Aden is the Executive Director of the African American Historical Society Museum in Fort Wayne. He remembers Martinsville, Indiana as an unfriendly place.

“You could not be caught in that county or anywhere near that town, even during the day, let alone at night.”

Aden said the beginning of Sundown Towns have ties to Pass Laws from the antebellum period before the Civil War. Pass Laws allowed enslaved African Americans to conduct business for their owners, which sometimes meant they were also allowed to travel after dark.

In the North, southern slave owners would travel with their enslaved people. Aden said many scholars believe Sundown Towns arose after the Civil War as a means of keeping Black labor in the counties where they lived, rather than allowing them the safety to move to new counties.

“Because, after the Civil War, many white Americans who had relied on enslaved African American labor were not intending to farm their own land or perform activities that they felt were beneath their station in life. And, so, that meant retaining Black labor.”

Some Sundown Towns had official legislation on their books to keep Black people out of their cities. But most, Aden said, were extrajudicial.

“A lot of African Americans would just know which towns were Sundown Towns or cities and which ones to avoid being in by nightfall.”

Today, some towns have officially removed Sundown legislation from their books, but many towns have swept the past under the rug. In his book, Loewen tells of asking local librarians if they saved the threatening signs or photos of them, and recalls them often laughing at the question, asking; ‘Why would we do that?’

This illustration from Kurt Vonnegut’s book Breakfast of Champions appears in Loewen’s own book. He wrote that Vonnegut, an Indianapolis native, grew up surrounded by sundown towns. Despite having evidence of more 100 towns in the Midwest and West with sundown signs, Loewen said Vonnegut’s illustration is the only visual he has from the area.

Credit JAMES LOEWEN, ‘SUNDOWN TOWNS: A HIDDEN DIMENSION IN AMERICAN RACISM’

In northeast Indiana, the city of Huntington has been documented as a confirmed Sundown Town on Loewen’s website. Huntington Mayor Richard Strick said, while the city has come a long way, a lack of documentation can make having conversations about that time difficult and hard to relate the current environment to the city’s past.

“Even before you get into people feeling like they’re not responsible for what happened here historically and the various tensions that we’re all living through in our nation right now and trying to have these conversations.”

In 2009, Huntington unveiled a new mission statement which mentions its citizens’ “ethnic, economic and religious diversity provides the strength that holds our community together” and says it is a “community of civility and inclusion where diversity is honored.”

Strick said he thinks the adoption showed the city trying to move forward from that checkered history, but that it’s an ongoing challenge to make sure that everyone in the community feels represented and welcomed.

“Not only included but helping to lead our community and I think that’s a challenge everywhere. That I think, again, the dynamics here being a nearly all-white community are unique, but the underlying tensions and dynamics, they come out of the same place. And so, how to do we embrace this? How do we work through this? How do we allow ourselves to be challenged?”

Loewen has also written about the portrayal of Sundown Towns in entertainment. He said he knows of five movies that talk about Sundown Towns, — including recent Academy Award winner for Best Picture, Green Book – all of which set these towns in the deep South.

“And then, on the other hand, famous movie made in Indiana, Hoosiers. That’s about, among other things, it’s about the basketball team in Milan, Indiana, which was a Sundown Town, which beats another basketball team from another Sundown Town, and they’re playing in the sectional part of the statewide tournament in Jasper, Indiana, which was a third Sundown Town. And yet, Hollywood never mentions this. Indeed, they put a couple of Black folks in the crowd scenes.”

Loewen keeps a running website of confirmed and suspected Sundown Towns and encourages visitors to help him confirm towns.

“I think it’s very important for a couple of reasons. First of all, many people living in some Sundown Towns have no idea. And, of course, I’m saying many white people, Black people too don’t know. […] And people who don’t want to know, usually don’t know. So, it’s good to get the truth about the past out, because it takes away your illusions.”

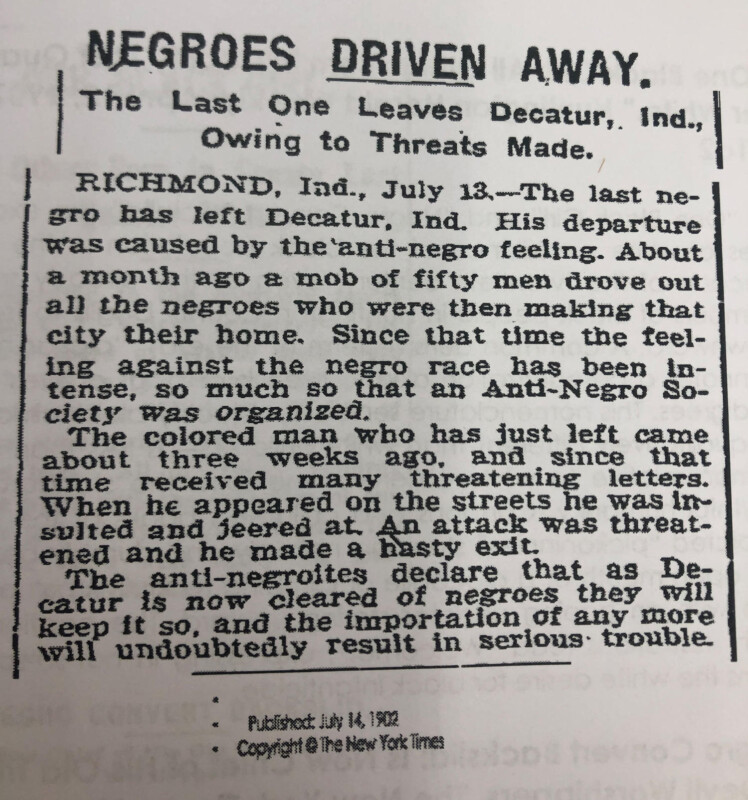

An article published in the New York Times in 1902 says a mob of men ran all the Black people from the town of Decauter, Indiana due to increasing anti-Black sentiment.

Credit NEW YORK TIMES

Why is it so important to chronicle this part of a town’s history? Loewen mentions Ferguson, MO as an example of what he calls ‘second generation Sundown Town problems.’ Ferguson was briefly a Sundown Town between 1940-1960. Loewen said the Black population was thrown out by the white population. Loewen said the separation was enforced by an overwhelmingly white police force which would ticket and harass Black motorists for passing through the town.

“Well, by the time Ferguson had the, shall we say, riots or demonstrations for which they are now famous, Ferguson was almost two-thirds Black. But it still had that, leftover from the Sundown Town day, police force. So, that’s an example of a second generation Sundown Town problem.”

Jakobi Williams is a professor of African American and African Diaspora studies at Indiana University and specializes in social justice, politics and civil rights. He explains the relationship policing had to Sundown Towns during their heyday, and how it relates to the distrust of policing we’re seeing today.

“So, for example, if a person – these are anecdotal, but these are real lived experiences – a person of color is in a particular location that’s classified as a Sundown Town, and the people of that community attack that person, the police will not arrest them. In fact, they may arrest the person who was attacked.”

Today, Williams said this translates as law enforcement who may harass people of color for being in areas they don’t think they belong in, by following them out of town, searching them without proper explanation or giving them tickets.

He said the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s and the Black Lives Matter movement we’re seeing today are mirror images of each other as they continue to fight for many of the same issues.

“The difference between the two periods now is folks are calling for defunding the police, whereas in the earlier generations, in the 60s for example and beyond, folks were advocating for community control of police. So, defunding the police and community control is still similar. Whereas, defunding the police is asking that those resources be allocated to certain entities in the community, so the community can police themselves. And in the 60s, having community control of the police was the same, having people who are from the community do most of the policing themselves to avoid these confrontations.”

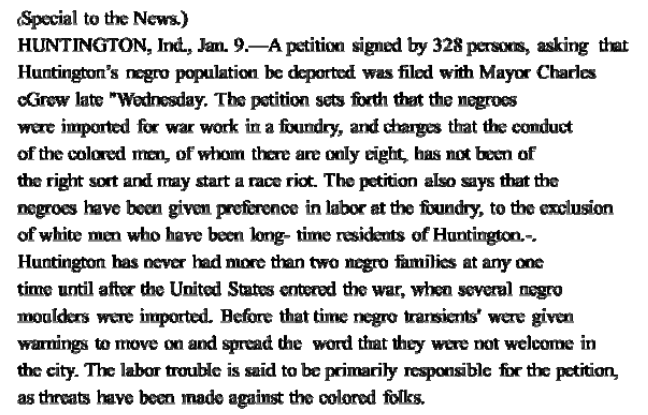

A story from the Fort Wayne News-Sentinel from January of 1919 talks about a petition filed with the mayor of Huntington to have the Black residents be ordered out of town. The article also states that, before the first World War, the town had never had more than two Black families because they would be run from town. (CLICK TO ENLARGE.)

Credit FORT WAYNE NEWS-SENTINEL

Loewen also said that the ongoing legacy of these towns is often misunderstood and damaging. He uses Kenilworth, IL as an example. Loewen said Kenilworth is the richest suburb of Chicago which, five years ago, didn’t have a single Black household. After hearing time and again that Kenilworth is just ‘too expensive’ for Black families, Loewen decided to do his own research.

“And I found that there are 7,000 Black households, Black families, that make more money than the median family does in Kenilworth. So, they could not only move into Kenilworth in terms of economics, they could move into the upper half of Kenilworth, into the larger houses. But they don’t.”

Still, the explanation of ‘just not rich enough’ not only persists, but is then passed down to younger generations to continue to sow the belief that people of color are economically inferior.

“So, we have to realize that we’re not talking about racism in the distant past. We’re talking about racism in the fairly recent past that still affects the fortunes of Black folks and white folks today.”

As protests took place across the nation at the beginning of the summer, Huntington, Indiana was not immune, even as a mostly white community. Mayor Richard Strick said they saw what was happening in other communities and were able to plan out a response to the protest.

He said Huntington’s law enforcement community recognized that people coming out to protest had a just cause and are passionate about justice.

Protesters march in front of the courthouse in downtown Huntington as part of the national Black Lives Matter protests that took place this summer on Wednesday, June 3, 2020.

Credit KEVIN KRAUSKOPF / CITY OF HUNTINGTON, IN

“We wanted to make sure that we supported them as they exercised their constitutional rights and freedoms and helped them to do so in a way that kept them safe and kept the community at large safe — also knowing there was likely to be, and there was, counter protestors.”

Strick said they were able to set law enforcement up in designated areas, intentionally dressed in casual clothing to make them more approachable to encourage dialogue. Their sheriff and chief of police were able to reach out to organizers and help plan things as well as supply water.

Strick said he believes the protest was a sign of progress for the city because of the number of people who showed up, but also that it means there’s still a lot of work to be done.