CAFOs’ Effect On Property Values Proves Challenging To Codify

Rural homeowners in Bartholomew County say a big, nearby hog farm – a concentrated animal feeding operation, or CAFO – is hurting their property values.

The county denied their bid to lower the CAFO neighbors’ property taxes, and argued the issue is too complex to codify, while residents say officials are just worried about politics and money.

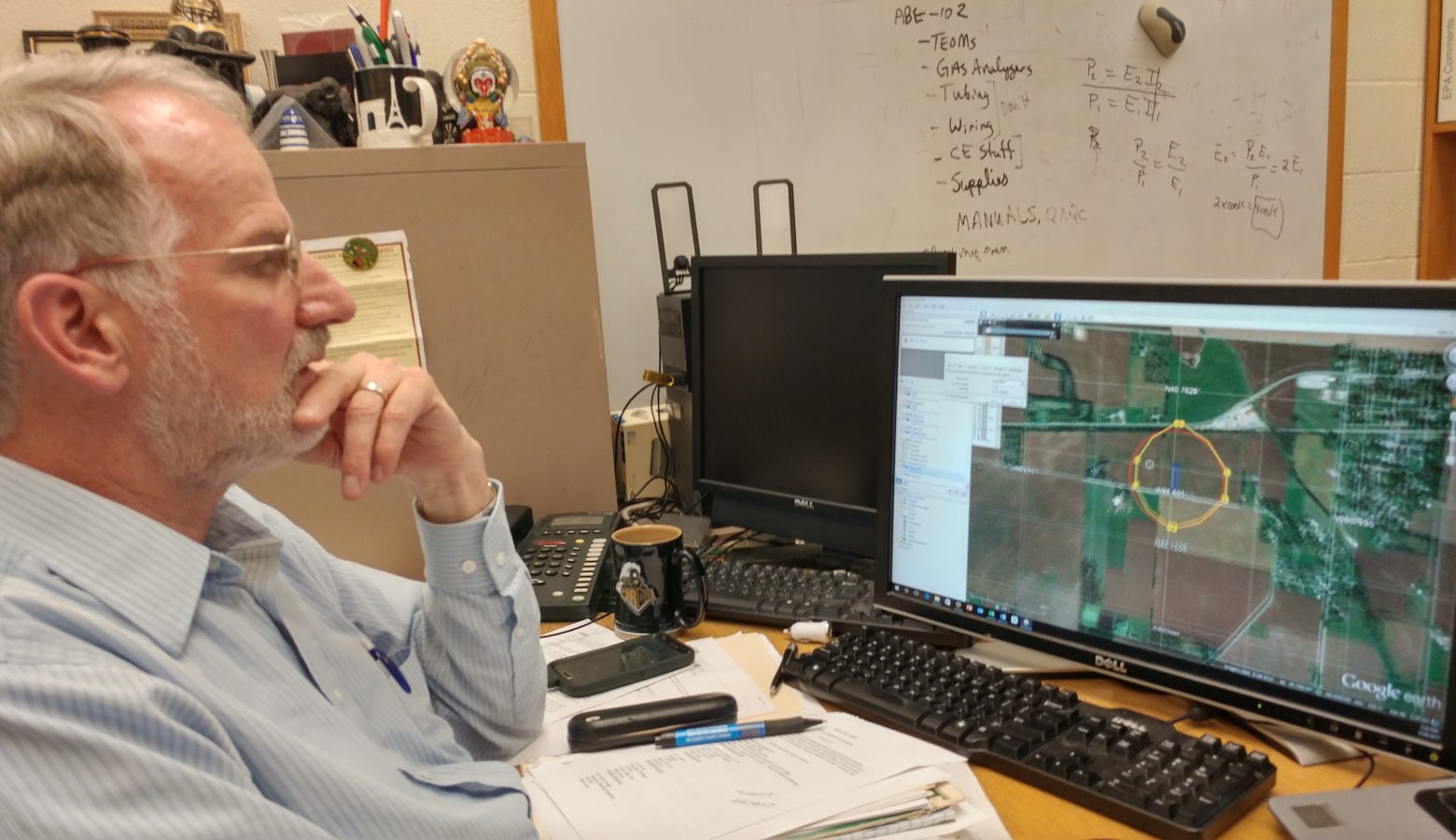

Bartholomew County assessor Lew Wilson has spent months working on property tax appeals with half a dozen residents in the tiny town of Hope.

His job was to help county appeals officials decide if the residents were right that their homes should be worth less – and their taxes lowered – because they live near a CAFO.

“We looked at these altogether, because we thought we had one problem,” he says. “But really, we have six people with individual situations.”

Wilson and his colleagues had hoped to devise a broader solution – an ordinance or change to county law – that would automatically lower the value of a house near a CAFO. This would have set a statewide precedent.

But Wilson says the law couldn’t just be about distance:

“You’ve got the lay of the land. You also have people that might be more sensitive than others,” he says. “There’s so many subjective things – and whenever you get into subjective items, it becomes more difficult, and then when you have several subjective items, it becomes even more difficult after that.”

Quantifying CAFOs’ Effects

It’s not so subjective to people like Al Heber, an agricultural engineer at Purdue University.

“Whenever there’s a controversy, I usually get calls,” Heber says. “People from both sides of the issue will download my model to see what my model says in terms of distance.”

His widely used computer model devises setbacks for houses near CAFOs: how far they have to be before the smell of thousands of animals and manure isn’t overwhelming.

The model comes in spreadsheet form, where anyone can plug in numbers, locations and geological features. It’s pre-programmed with the impacts of different animals, wind data from every Indiana weather station and the effects of abatement tools like trees or ventilation filters.

Once it’s filled in, it runs a formula Heber created and spits out an ideal setback between the CAFO in question and anything around it.

It shows these setbacks by plotting a rough circle around the CAFO on Google Earth. Heber says residents outside that circle will be pretty reliably safe from odor. Some counties have even used this process in creating their setback rules.

And Heber says he could adapt the model to talk about property values – with the right data. But that data doesn’t really exist.

For one thing, property values are driven by sales – and many real estate agents say homes near CAFOs just aren’t selling.

Either way, Heber says you’d need a lot of expensive, multidisciplinary research to pin down a variable for the model that describes property value impacts. And all that makes it hard to regulate.

“It’s difficult to do when you don’t have the data to back it up,” he says. “But it wouldn’t be the first time that regulations are put in place without science to back them up.”

Common Problems, Individual Solutions

Assessor Lew Wilson doesn’t want to take that chance.

“We’re gonna deal with it on an individual basis with an individual situation,” he says. “That’s how, I have finally determined, is the only way that I think I can settle these equitably.”

But the residents he’s been working with think that’s not the only reason.

Nancy Banta, whose family home in Hope is just half a mile from the CAFO, thinks the county is worried about losing tax revenue – and wading into politically thorny territory.

“If they start doing it with me, what’s going to happen is, they’re going to have to do it with a lot of people,” she says. “That’s what they’re afraid of.”

She hopes she and her neighbors will have better luck setting a precedent – even one by one – by taking their cases to the state. They filed appeals with the Indiana Board of Tax Review on Thursday.