Can Gary Schools Be Saved By A State Takeover?

Part I Audio

Part II Audio

Sharmayne McKinley, the principal at Daniel Hale Williams Elementary Schools in Gary, walks with students on Nov. 28, 2017. McKinly believes the state takeover of the school district will lead to positive results because of the leadership of the emergency manager Peggy Hinckley. (Eric Weddle/WFYI Public Media)

The Gary Community Schools Corporation faces massive debt and academic failures. In a last-ditch attempt to save the schools, state lawmakers took the extreme option last year to take it over by using laws that transferred financial and academic control to a state-hired emergency manager.

It was a controversial move that lawmakers hoped would give Gary Schools a second chance even as decades of decline in population and industry continue to drag down the district’s enrollment and state funding.

But there’s little evidence to say whether this method can save a school corporation on the brink. Other urban districts in similar situations have struggled under intervention for years with varied results.

More than 10,000 students have fled the district in the past decade for charter schools or nearby city schools. Today enrollment has fallen to around 4,700 K-12 students.

The person expected to fix it all is Lake County-native Peggy Hinckley, the emergency manager. To save the corporation — she must reinvent the district by consolidating schools, reshaping academic programs and attracting new students. It’s more than finding savings.

“If I’m not successful it would mean that the district is, I don’t know what they would do, I guess they have no other options but to dissolve it,” she says. “And you know I certainly don’t want that to be the period of my career.”

For the past six months, the 65-year-old education veteran has been the sole decision maker for the district. Hinckley’s office in the district’s Polk Street headquarters is sparse and quiet. On her desk are a phone and a swatch of memos and documents. On this day, there is no computer. The office is just a few hundred feet away from one of the city’s 28 abandoned schools. It’s a reminder of the decades-long struggle of the city.

The population here has fallen by 40,000 since 1990 to 76,400 in 2016, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

“First of all, anything anyone would have told me about it was much worse than I would have expected,” she says of the physical and academic condition of the system’s 12 reaming schools when she arrived in August.

Improving academics is a key priority, Hinckley says. More than 80 percent of Gary students failed both parts of the 2017 ISTEP exam. This week state education officials alleged cheating by staff took place on those tests at one school.

But what could be a more significant fix is digging out of an enormous deficit and years of mismanagement and lack of fiscal controls cited by state auditors.

Peggy Hinckley is the state-hired emergency manager for the Gary Community School Corporation. The former Indiana superintendent and Lake-county native sits at her desk in the district’s main office. (Eric Weddle/WFYI Public Media)

By the end of February, Gary Schools Corp. will be $115 million in debt. It owes the IRS $7.1 million, not including fees and interest, for skipping on paying payroll taxes in 2013. It owes more than $2 million to utility companies, including $1 million to gas company NIPSCO.

The state gave MGT Consulting Group, based in Tallahassee, Fla., a $6.2 million contract to serve as Gary’s emergency manager. Hinckley has a team of 12-15 people working on the emergency management. The contract calls for Hinckley to make compelling improvements in the classroom and the accounting books. Financial incentives worth nearly $1.5 million are available if she meets fiscal and academic benchmarks.

In 2019, lawmakers will decide if Hinckley gets a third year.

“So we have to produce,” she says, “And we have to produce in a year.”

Since August, Hinckley has chipped away at overspending. So far she’s saved around $2 million — from small layoffs, ending overtime, and renegotiating the district’s health care plan. But it’s nowhere near enough. In December and January, she did not need to request loans from the state to cover payroll as she did in past months. For most of last year, the district was running $2 million over budget monthly.

Hinckley’s “deficit reduction plan” — including school closures and grade reconfigurations — will become public Friday at a meeting of DUAB, or the state’s Distressed Unit Appeal Board. The board has oversight of the emergency manager.

She expects many to be angry.

“Because I realize it will be a very emotional topic. So I think there’s always emotion involved in school closings,” she says. “But again our survival depends on it.”

‘Don’t Sacrifice My Child’

On a late-November school night at Nina and LeBarron Burton’s home, three of their four children are practicing on their string instruments.

The three attend William A. Wirt-Emerson — a visual and performing arts academy that could be closed as part of Hinckley’s cost reduction plan.

“Our hope was to have them all graduate from Wirt-Emerson,” Nina LeBarron says.

Unlike a growing number of other families in Gary, the Burton’s want to stick with the city schools.

Nina and LeBarron Burton talk in their home in Gary, Indiana about their concerns of the state takeover of Gary Community School Corporation on Nov. 27, 2017. (Eric Weddle/WFYI Public Media)

More than 500 students left the district in the wake of the takeover last year, and more than 60 percent of K-12 students who live in Gary have chosen to attend a charter school or nearby city school instead of the district.

But the Burton’s chose to bring their kids back after sending them to a charter school because they want their tax dollars to support it.

“I want to strengthen this community,” LeBarron Burton says. “But in order for me to strengthen this community, I don’t want to sacrifice my child to a system or a process that hasn’t been figured out yet.”

The Burtons are concerned Gary could follow in the steps of Detroit Public Schools. That district cycled through four emergency managers during eight turbulent years of state intervention.

They are also concerned about the power of Hinckley. Nina Burton says it doesn’t seem right the emergency will choose which schools to close and what staff to lay off.

“I don’t think it’s fair for one person to have a decision making authority or power especially if that person is not going to be open,” she says. “If there is going to be changes, I know me and my husband we’re not against that but we want what’s best.”

No Magic Bullet

There’s little evidence to say any one type of state intervention can reform a school corporation. In addition to the single-emergency manager, also known as a receivership, other turnaround models involve mayor’s offices or collaborations with charter school operators.

But experts say there are too many variables to improving student achievement and reversing financial problems to say if or how one approach will work.

“It’s not a magic bullet,” says Nelson Smith, a consultant who studies state takeovers and former CEO of National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. “I wouldn’t say that receiverships work period. I think it does depend very heavily on the quality of leadership.”

Emergency managers who Nelson views as helping pulled districts from the brink — such as in Newark and Camden, New Jersey — took a holistic approach and worked with their communities.

“People like that who are imaginative, who are really driven and who are collaborative,” Nelson says. “You know that that’s a good start.”

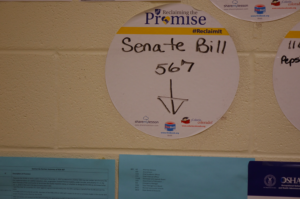

A sign with the Indiana State Law about the takeover of Gary schools hangs in the teacher’s lounge at Daniel Hale Williams Elementary School. (Eric Weddle/WFYI Public Media)

Larry Eichel, director of Pew’s Philadelphia research initiative, says there’s just not much research yet to show what the right, or wrong way, is for a state to takeover a district.

What educational experts generally agree on, he says, is that there is an improvement by the takeover operator on the financial ill or perceived mismanagement that caused the takeover in the first place.

“But there is not any evidence that any particular system of governance for an urban school district is superior to any other when it comes to performing long-term academic performance,” Eichel says.

While research doesn’t point to what type of takeovers are sure to work, there’s agreement that a clear policy for who is in charge — like Gary’s emergency manager — is beneficial.

“A clear governance system with clear lines of authority is preferable,” Eichel says.

‘A Milestone’

Sharmayne McKinley, the principal at Daniel Hale Williams Elementary Schools, remembers how she felt when the state took over the district.

“Thank you. We need help. So if someone can come in and do something different than what we had — it couldn’t hurt,” McKinley recalls. “I mean, we were already screaming for help, so I had an open mind. I’m sure a lot of us did but some of us didn’t.”

Until the takeover, McKinley says, the math and reading textbooks at Gary schools were 10 years old. To preserve the books, she says, students were prohibited from writing in the books. Or teacher made copies of the pages for use.

The shuttered David O. Duncan Elementary School is on the same block as the district office for Gary Community School Corporation. It is one of 28 abanonded school buildings in the Gary public schools district. (Eric Weddle/WFYI Public Media)

“Then the copy machine broke down. So we had teachers going out, paying for copies, buying copy machines for the classrooms,” McKinley says.

One of Hinckley’s first actions was to spend around $1.2 million in federal Title 1 funds on new books for the entire district.

“You’d have thought we were little kids in the candy store getting supplies for our kids,” McKinley says. “That was a milestone.”

Another challenge teachers and schools leaders faced was the lack of a district-wide academic officer. The school board got rid of the position. McKinley and other current Gary Schools staff say they had to seek out the state’s academic standards on their own or ask for help from teachers in nearby cities.

“So we asked other districts,” McKinley says. “They went out and ask ‘who can loan us something so we could have a roadmap?’”

Today, teachers follow the 8-Step Continuous Improvement Process. It combines student data, regular assessments, and remediation. It’s not uncommon to use these methods — but it’s never been done in Gary.

Hinckley used the process when she was superintendent at Warren Township in Indianapolis. The program led to academic gains and national recognition.

At Gary she’s introduced curriculum maps, similar to pacing guides, to ensure students are learning the state standards. Students are assessed every week three weeks to gauge if they are learning on pace or need extra help. The students who are falling behind get extra attention.

“So it’s the idea of — you kind of scoop them up every three weeks provide some remediation and then help them,” Hinckley says.

Two elementary schools also offer extended days in an attempt to shift the chronic academic failures there. Last year, less than 3 percent of students at Beveridge and 13 percent of students at Jacques Marquette passed both parts of the ISTEP exam.

“We feed them dinner and then they have two hours of tutoring,” Hinckley says. “This is voluntary for parents. We have a number of children participating in those particular schools because their achievement was so egregious.”

Four retired Indiana administrators work part-time as curriculum support staffers. They visit each school monthly to ensure implementation of Hinckley’s academic initiatives and offer help.

“But if no one ever checks on it you know the likelihood of it working well is small,” Hinckley says.

‘Going Sky High’

During a lunch break at Williams Elementary Joy Cheatham — a first-grade teacher with 25 years experience — says she is still getting used to Hinckley’s changes.

The combination of new textbooks and the “eight steps” process is a lot to absorb and feel comfortable using in the classroom.

“I think we needed more training in it. They kinda threw it on us,” Cheatham says. “I think that is what makes for a late night cause we are trying to figure out what we need to do, and how to plan.”

But Cheatham says the new materials, supplies, and curriculum is enough to help the children.

“We just go to put in the work on our part,” she says.

First-grade teacher Joy Cheatham asks a student to respond to a question during a reading class at Daniel Hale Williams Elementary School in on Nov. 28, 2017. (Eric Weddle/WFYI Public Media)

Principal McKinley says it’s all working.

The once top-rated Daniel Hale Williams school is now rated an F by the state. But McKinley is hopeful that will change after this year.

“This year my test scores are really going sky high,” she says. “I am claiming it — they are going to go all the way up. Seriously.”

For 2018, McKinley proclaims, her school will be a C — at the least.

A ‘Change Agent’?

It’s too early to evaluate Hinckley’s six months on the job. But some state lawmakers, such as Rep. Tim Brown, chairman of the powerful House Ways and Means Committee, say they’re pleased with savings Hinckley is making, such as building maintence that has lead to lower water and sewer bills.

“Looking under the hood and taking care of nuts and bolts has made a difference for kids,” Brown says.

But Rep. Vernon Smith of Gary views Hinckley differently. Many in Gary, he says, are frustrated with the loss of local control.

“My people feel like they have no voice now,” he told the House chamber during a debate on Feb. 1.

A 2012 law made this state takeover possible. A seperate 2017 law, Senate Bill 567, was directed at Gary and a lesser intervention for another troubled district, Muncie Community Schools.

The state took over Gary Schools in August. The two laws gave Hinckley as the emergency manager, absolute power over the district. That means, the Gary superintendent and elected school trustees are reduced to advisors.

Gary Superintendent Cheryl Pruitt whispers to school board President Rosie Washington during a meeting of school trustees on Nov. 28, 2017. Both have since resigned. (Eric Weddle/WFYI Public Media)

Angered over their loss of power, Superintendent Cheryl Pruitt resigned earlier this month and school board President Rosie Washington resigned at the end of December.

Other school trustees have complained. Robert Buggs, the board vice president, says he doesn’t think the school board’s position on school closures or layoffs will be considered.

“We are not being consulted with when someone puts something in front of you and says decisions have been made,” he says. “That’s not consulting – not in any dictionary I read.”

Smith says some in the Gary community don’t trust Hinckley because of the fast-paced changes she has made and expected to come.

“She has not been able to be a change agent. She has gotten resistance because she is not engaging the community,” Smith says. “Part of being a change agent means not moving too fast. People are afraid of the unknown.”

Hinckley disputes that she is not engaged. In addition to monthly school board meetings, there’s been two public forums and two different community meetings in January, and other events, she says. Twice a month, WLTH 1370 AM hosts Hinckley for a call-in show.

Principal Sharmayne McKinley says parents at her school are seeing the improvements and understand it is because of Hinckley.

“Dr. Hinckley and her team are really doing a great job having forums with parents and having them ask questions,” she says. “And I just love that.”

For Gary to return to local control, the district must have two consecutive years of positive cash flow and vendors need to be paid off. A recent state audit report found the district owes vendors $16,971,524 as of July 2017.

A key to getting to that point, Hinckley says, is figuring out what the right size of Gary School Corp. should be going forward. At the least, it will mean consolidating schools.

“I do think all of our folks understand the urgency,” she says. “That our life is on the line in Gary.”

Hinckley will present her deficit reduction plan 9:30 a.m. Friday to the Distressed Unit Appeal Board in Conference Rooms 4 and 5 of the Indiana Government Center South Building, 402 West Washington St.

Contact WFYI education reporter Eric Weddle at eweddle@wfyi.org or call (317) 614-0470. Follow on Twitter: @ericweddle.