Red For Ed: How Teacher Action Unfolded At The Statehouse And What Comes Next

It’s a Tuesday morning, just before 7. It’s still dark outside and a group of more than 20 teachers from Bedford, just south of Bloomington, are getting on a school bus. They’re going to the Statehouse.

Anna Wall is sitting toward the front of the bus in a thick red hat. She’s an elementary school special education teacher. She’s talking with some of the other teachers about different shades of red they have on and what today means for them.

“This isn’t something I go to, I don’t go to state rallies. I mean, I’d rather be in the classroom,” Wall says.

Wall says she doesn’t follow policy really, but she’s seen changes in the classroom. She’s joining some 15,000 fellow educators as they call on lawmakers for things like better pay and equitable funding for schools. They also want fewer tests to evaluate kids, schools, and teachers. Wall says, the pressure that comes with taking state tests for the first time in third grade can be really hard for students to grapple with.

“I had one little girl that knew that she wasn’t up to par with her grade level – third grade – and she knew she was doing second grade was more where she was at, and she just cried,” Wall says.

Schools in nearly half the state’s districts were closed as educators converged on the capitol. For many, including Wall, the stakes were too high to stay home.

“I think I wanted to say that yes I stand for something I stand for a teacher I stand for all of my colleagues and that we are working hard,” Wall says.

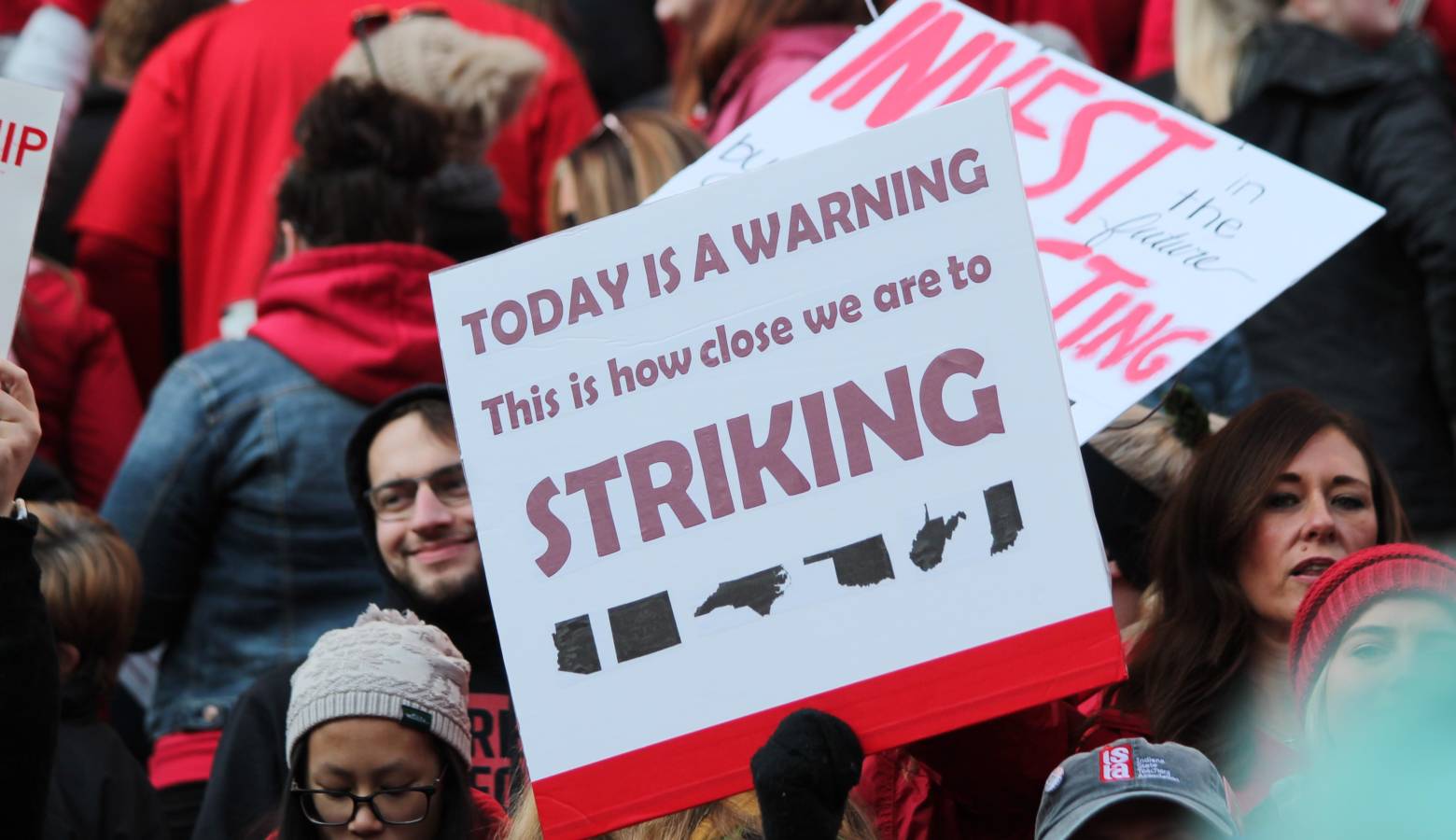

Fast forward to later that morning. The sun is up and a wave of red-clad public school educators and supporters fill the Statehouse and the lawns outside carrying signs and chanting different messages of frustration, hope, and power. They even have a marching band blasting music fitting for a pep rally. It’s the same day lawmakers return for the ceremonial start to the legislative session. The rallies echo through the building and outside for most of the day, reflecting a national movement called Red for Ed.

Many say contentious policy changes and underfunding of public schools over the past decade led us here. With the state sitting on a massive surplus, teachers say it’s time for legislators to invest in better salaries for school staff, and more resources in the classroom.

Vigo County School Corporation teacher Diane Burpo says when she graduated from college in 1992, she had to actually leave Indiana to teach because there were rarely openings. Decades later, she says it’s a totally different story.

“When we look at teacher pay in other states that are around this region, every single state is paying higher than we are, we are losing some of our best teacher candidates,” she says.

As State Superintendent Jennifer McCormick spoke to a crowd of reporters outside of her office, a few dozen teachers already inside the Statehouse gathered to listen.

“We are not asking for the moon, nor are the teachers who are here,” she says. “We are here asking for the basic foundations that make an education system great, and in turn make a state great.”

One of those foundations is funding. House Education Committee Chair Bob Behning met with a group of teachers earlier in the day. He says right now, money matters are a tough ask.

“This is not a budget year, so historically, we have not opened the state budget,” Behning says.

He says lawmakers are ready to listen as they re-work school measures of accountability, and, consider a second look at a new and controversial licensing requirement they approved last session.

Many educators say they feel disrespected and unheard by lawmakers in the Statehouse too. Behning says he thinks more, clearer communication could help ease that tension.

“I will say that there is a lot of blame that we need to be accepting as well, that we need to be more open to having dialogue and I’m not opposed to talking to teachers about where I am and where they are and let’s see if we can come together,” he says.

Teachers are already coming together in a way. McCormick has encouraged educators to wield their voting power, and has been increasingly vocal about their concerns heading into her final year as the state’s chief of schools.

“Our students deserve every bit of this advocacy that you see, but it is a shame it takes this type of advocacy to get what they deserve,” McCormick says.

Educators hope to carry that kind of energy into the 2020 elections.

It’s hard to say how different legislative races could play out with a freshly fired up base of teachers. But next year’s race for governor is a big one: the winner will choose McCormick’s successor – appointing the state’s chief of schools for the first time.

Teachers like special educator Anna Wall hope someone will champion their needs in the Statehouse.

“I want respect, I want, you know, all the years of education that I do and all the training that I do on my own naturally, that it counts for something,” Wall says.

And to get it, the crowd made it clear: they’re ready to take their frustrations to the ballot box next November.

Contact Jeanie at jlindsa@iu.edu or follow her on Twitter at @jeanjeanielindz.