Violence Is A Growing Problem At Indiana’s Miami Prison, Data Show

The Miami Correctional Facility is getting more dangerous.

As Side Effects previously reported, former employees said the Indiana men’s prison is out of control. Housing units are so short-staffed that officers can’t quickly respond to emergencies like stabbings, let alone prevent such violence from occurring.

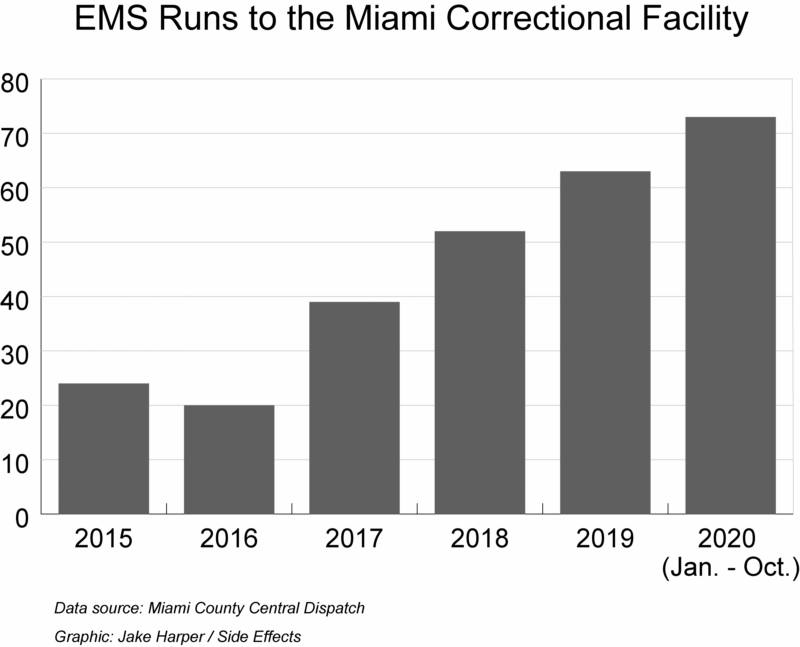

Data from the Miami County Central Dispatch reinforce that image. Ambulance and helicopter runs to the facility have more than tripled since 2015. Though 2020 is not over, the number of incidents at the facility has already surpassed previous years: Emergency medical services visited 73 times from January through October.

At least 29 of those visits resulted from trauma or violence, such as stabbings. The true number of violence-related ambulance runs may be even higher, since another 28 incidents were given vague labels such as “medical.”

“Almost daily there’s some sort of violence,” said a current employee at the prison who asked to be identified by an initial, R, because he didn’t have permission to speak with the media. “The ambulance has been at the prison quite a bit this year.”

And the EMS runs only hint at the disorder in the prison. Medical staff in the infirmary treat less severe injuries, so the prison may never call for an ambulance in those situations.

Indiana Department of Correction officials declined requests for interviews and documents related to violent incidents at the prison. In an email, Miami spokesperson James Frye attributed the rise in violence to a shift in the inmate population after 2017.

“The facility transitioned to housing a majority of maximum security offenders, many of which have been sentenced for violent acts,” he wrote.

Frye’s statement did not address how the prison’s safety was affected by staffing levels, but former staff said the lack of personnel played a significant role. Officers are drastically outnumbered in the housing units, each of which can hold more than 200 men.

“We’re supposed to have eight people running a house,” R said. “We’re lucky if we have two.”

Warden Bill Hyatte took over the prison in March 2018. That month, the facility had 375 custody staff — officers, sergeants and others responsible for the safety and security of the prison. By March 2020, that number had fallen to 315 and it continued to drop through September to 266. The facility had 176 vacancies that month, according to the latest available report.

The staff members who spoke with Side Effects blamed much of the outflow on prison management.

“A lot of people are just fed up with it and just tired of the way it’s been run,” R said. “It is very much a top-down problem.”

Former employees said they were consistently made to work 16-hour shifts. The stress contributed to their mental health problems, including anxiety, depression and even suicidal thoughts — issues that are well documented among correctional workers.

Even so, the former staff said the prison administration handled such issues poorly. Two told Side Effects their superiors, including warden Hyatte, were dismissive of their suicidal thoughts. One said he was forced to resign when a captain refused to approve unpaid leave for mental health treatment.

“Paramount among Warden Bill Hyatte’s concerns is the safety and welfare of offenders and staff members at the Miami Correctional Facility,” wrote Frye.

After R started his job earlier this year, many units were locked down for long periods not because of COVID, but because the facility was so short staffed, he said. Even with prisoners mostly confined to their cells, the violence continued.

R witnessed some events personally. He described an incident in which one man stabbed another, and within two months, one more. One of the victims needed to be flown to the hospital, R said.

He heard stories from other units, too. One inmate had his finger cut off, supposedly over a small debt. Someone lit a fire in the restrictive housing unit, where inmates are held in solitary confinement, using a makeshift lighter. (The dispatch data show a fire-related call on Oct. 6.)

And sometimes, R said, fists or weapons were aimed at staff — usually when the men feared an attack from other inmates.

“When they attack a CO, it’s not because they have a problem with a CO,” they said, adding that inmates who attack officers are often moved to the restrictive housing unit. “They see a way out of the current situation they’re in.”

Asked why the department continued to shift more maximum-security inmates to the Miami prison, given its worsening staffing and violence issues, Frye replied in broad terms.

“The Indiana Department of Correction evaluates each offender to determine their program needs and security level for placement in an appropriate facility,” he wrote.

Meanwhile, the agency has taken steps to bring in more officers. There have been several virtual recruiting events, and its homepage and social media accounts advertise the opportunity to work in state prisons. Frye wrote that a recent pay increase for officers — from $16 to $19 an hour — has helped the department hire more people.

R has noticed some new faces at the prison, but wonders how long they’ll stay.

“I don’t get too excited about it,” he said. “Since I got hired in, they’ve brought in several classes, and most of them have quit.”

R likes the pay raise but he’s applying for jobs, looking for a way out.

This story was produced by Side Effects Public Media, a news collaborative covering public health. Jake Harper can be reached at [email protected]. He’s on Twitter @jkhrpr.