While in seclusion, he completed a standardized test, fell asleep multiple times and, in one seclusion incident in March 2022, school staff wrote that they believe he may have had an absence seizure — a brief seizure that causes a lapse in awareness — according to school records. The boy is diagnosed with epilepsy, but Swinehart said school employees never notified her about the suspected seizure.

“It’s heartbreaking. I feel like I’m failing him,” Swinehart said while fighting back tears during a recent interview. Swinehart learned of the suspected seizure months later and only after getting school records. “You’re supposed to be able to trust that your school is a safe place to be.”

Swinehart’s son attends Warsaw Community Schools, a district in north central Indiana. WFYI is not publishing his name because he is a minor.

Swinehart said her son loves to learn — he’s especially interested in math and science — and had done well with a former teacher. But when that teacher left, his behavior deteriorated and school district officials transferred him to a special education program at Claypool Elementary School.

After repeated bouts of seclusion and physical restraint by Claypool staff, he now dreads going to school.

“He would cry and just say over and over again how much he hated school,” Swinehart said. “[The seclusions and restraints] had a horrible effect on him. He’s traumatized. He can’t sleep in his own bed. I don’t think he’ll ever like school again.”

Swinehart’s son isn’t the only student in Indiana traumatized through the experience of seclusion and restraint in schools.

Students across the state are secluded and restrained thousands of times each year, according to data provided by the Indiana Department of Education.

The state defines seclusion as the confinement of a student alone in a room or an area from which they’re physically prevented from leaving. Physical restraint is defined as physical contact between a school employee and student that involves the use of a manual hold to restrict freedom of movement of all or part of a student’s body.

Indiana lawmakers approved legislation a decade ago that was intended to regulate and curb the use of restraint and seclusion in schools.

The law states that these interventions should be used rarely, and only as a last resort in situations where the safety of students or others is threatened.

But a lack of oversight from the Indiana Department of Education means it’s unclear whether the law has had its intended effect.

The DOE collects district-reported data on the number of incidents of seclusion and restraint in schools.

But a WFYI investigation — based on public records, court documents, internal school logs, audio recordings of state-level meetings, and parent interviews — found that some schools do not accurately report incidents of restraint and seclusion to the state.

The DOE is also required to conduct an annual audit of seclusion and restraint data reported to the agency by school districts, according to a rule that took effect in 2018.

But the department has no record of an audit ever being done for the previous four school years, according to a spokesperson for the agency, Christina Molinari.

“Personnel changes over the last year led to a shift in responsibilities over the commission, which has delayed an audit,” Molinari wrote in an email. In response to WFYI’s inquiries, Molinari wrote that the DOE is now conducting audits for the last two school years and will conduct an audit for the current school year.

State requirements with no enforcement

School districts, charter schools and accredited private schools are required by state law to adopt a restraint and seclusion plan.

Interviews with parents across the state also show that schools are not always following their own policies. Children have been injured during seclusion and restraint incidents, leading some to remove them from school out of a concern for their safety.

Every school’s restraint and seclusion plan must stipulate that:

- Restraint and seclusion must only be used as a last resort and in situations where there is an imminent risk of injury to the student or others.

- It should only be used for a short period of time, and be discontinued as soon as the risk of imminent injury has passed.

- Every incident must be documented and reported to a student’s parent or guardian before the end of the school day or as soon as practical.

Some districts — including Warsaw Community Schools where Swinehart’s son is enrolled — have adopted plans that go beyond what’s required, by including a statement that seclusion and restraint shall never be used as a form of punishment or as a matter of convenience.

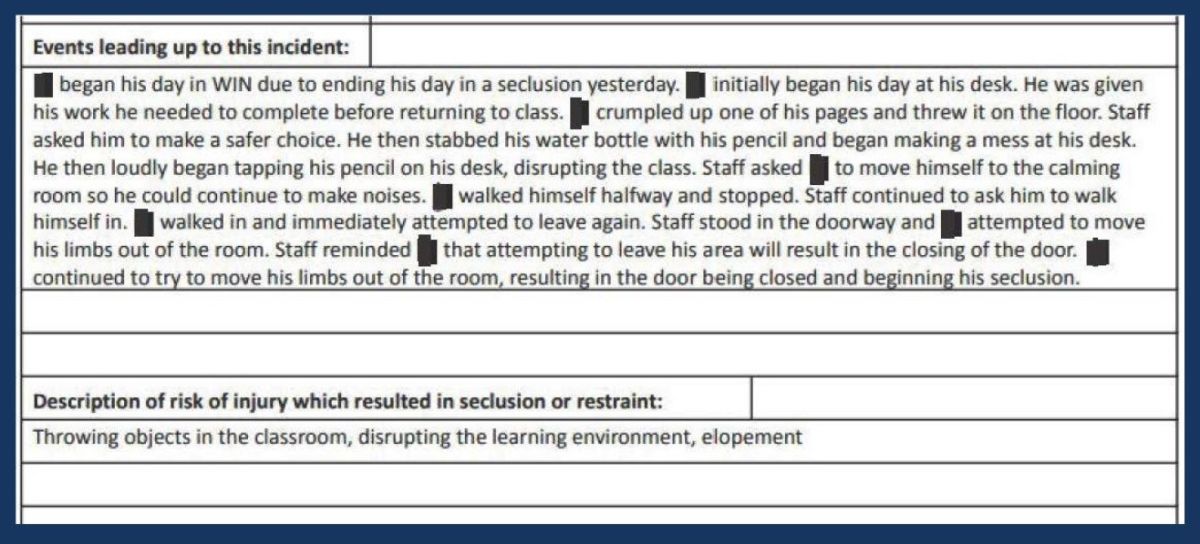

But Swinehart’s son was secluded for not following directions. And, on one occasion, he was secluded for roughly six hours because he threw a piece of paper on the floor, stabbed a water bottle with a pencil, tapped his pencil on a desk, and attempted to leave the seclusion room, according to school records.

This is a copy of a seclusion report for Swinehart’s son. He was secluded for roughly six hours that day.

A WFYI investigation has found that the DOE hasn’t held schools accountable for violating their restraint and seclusion plans.

Molinari wrote in an email that the DOE does not have the power to make schools follow these plans.

Special education advocates have long been concerned about the use of restraint and seclusion in schools. Nationally, students with disabilities are disproportionately subjected to these practices: 77 percent of students secluded and 80 percent of students restrained during the 2017-18 school were receiving special education services, according to data from the U.S. Department of Education.

While these interventions are used tens of thousands of times per year in schools across the country, they carry the risk of injury and, in rare instances, death.

The federal government doesn’t track deaths or injuries related to seclusion and restraint, and there is no federal law governing their use in schools.

‘The commission is stagnant’

The Indiana Commission on Seclusion and Restraint, established by the 2013 law, was tasked with drafting rules and creating a model plan that details how schools should report and use these interventions.

But now, two commission members say the body has lost focus. Commission members debated their purpose and intended role during meetings between 2019 and last year.

The DOE did not respond to multiple requests for an interview with Stephen Balko, an employee at the department and chairman of the Commission on Seclusion and Restraint. Six current members of the commission declined to comment or did not respond to an interview request.

Kim Dodson, CEO of the Arc of Indiana — an advocacy organization for people with disabilities — has served on the commission since its inception, and she was one of the advocates who pushed legislators to pass the 2013 law. Dodson said she routinely received calls from parents who were upset about their children being restrained and secluded in school. Since the law took effect, she said the volume of calls has decreased.

“But that doesn’t necessarily make me feel good and make me believe that it’s not happening,” Dodson said. “I just think that parents don’t know that it’s happening. And I still think that schools are utilizing it far too much to take care of what they think are disruptive students.”

The commission drafted rules on how these interventions should be used — with an emphasis on decreasing the use of seclusion and restraint in schools — including the requirement that schools report the number of incidents of restraint and seclusion by both employees and school resource officers in their annual performance report.

Dodson said the commission “put forth some very strict guidelines.”

John Elcesser, a founding commission member, said “they took seclusion and restraint to the front burner for many schools.”

But Elcesser, executive director of the Indiana Non-Public Education Association, said the commission has struggled to find its objective in recent years.

“I do think that the commission served a really good purpose at the front end in creating templates for how to create a seclusion and restraint plan,” Elcesser said. “I think we probably have not been as good in terms of the data issue.”

Elcesser and Dodson point to staff and administration turnover, as well as a lack of ownership of the commission by the DOE, to explain why problems in data reporting and a lack of accountability for seclusion and restraint at the district-level continue to exist.

The commission has existed during the elected terms of two former Superintendents of Public Instruction, Glenda Ritz and Jennifer McCormick, and now under Gov. Eric Holcomb’s appointed Secretary of Education Katie Jenner.

“The commission right now is just stagnant and not getting utilized the way that we want and should be getting utilized,” Dodson said.

WFYI requested comment from the DOE regarding Dodson’s characterization of the commission. They did not respond.

The commission has no enforcement power to ensure districts are accurately reporting incidents and following their restraint and seclusion plans.

Inaccurate reporting

Just a few days into the August 2018 school year, Emme got a call from her son’s school nurse. She was told her kindergartener had fallen and hurt himself after being placed in a room alone.

WFYI is withholding Emme’s full name to protect her family’s privacy and because she fears retaliation from her son’s school district.

Emme’s son attended George L. Myers Elementary School — part of the Portage Township School system in northwestern Indiana. Her son is on the autism spectrum and has ADHD, among other conditions. Emme said he was placed in a classroom at the elementary school with children who had a variety of behavioral issues and needs.

Emme said her son has impaired language and memory skills, and will sometimes experience episodes of screaming outbursts.

“But he wasn’t a fighter, like that’s never been him,” Emme said.

Emme said she was told that school staff had removed her son from his classroom and put him in a separate room by himself because he was pacing. She said school staff didn’t clearly explain how her son injured himself while alone in a room.

“They said he paced and slammed his face against a wall,” she said. “It just made no sense.”

Emme took her son to a hospital because his nose wouldn’t stop bleeding. He was diagnosed with a nasal fracture, according to medical records reviewed by WFYI.

Due to concerns for his safety, Emme pulled him from the school and enrolled him in a virtual school.

Superintendent of Portage Township Schools Amanda Alaniz said in an email that she is unable to comment on “individual cases of student discipline.” She wrote that seclusion is not a common practice in PTS, and that staff have been advised to only use it in the “most extreme cases to preserve student and staff safety.”

Alaniz wrote that school employees are “instructed to follow a process of reporting to their building principals for input into our district’s student information system,” and that information is reported to the state.

Emme eventually enrolled her son in another school within the same district.

“I’m always dreading and terrified that something’s going to happen, that he’s going to end up put in there, like put into a seclusion room again,” she said. “It’s sad. It scares me.”

‘Worried about the zeros’

Portage Township Schools — a district that serves roughly 1,200 students with disabilities — reported zero incidents of seclusion to the DOE for the last five school years, including for the 2018-19 school year when Emme’s son broke his nose after being placed in a room by himself.

Emme believes that PTS failed to report her son’s seclusion to the DOE.

It’s a worry that’s shared by multiple members of the state commission. Since at least 2019, commission members have expressed concerns to DOE staff that schools are not accurately reporting seclusion and restraint incidents, according to recordings of commission meetings provided by the DOE.

“We really wanted the Department of Education to take a strong interest in this and to really be the people policing the data,” Dodson of the Arc of Indiana said in an interview. “Our intent was: let’s look at trends, do we see high incidents of seclusion or restraint in a certain school, and then can we get more training to that specific school.”

But Dodson and other commission members believe there is significant underreporting of seclusion and restraint by schools. She said the data collection is “clearly not working, and I think we need to revisit that. And perhaps that needs to be revisited legislatively.”

Roughly 69 percent of school corporations and charter schools reported zero incidents of seclusion and about 46 percent reported zero incidents of restraint last school year. The share of schools reporting zero incidents of seclusion and restraint have remained relatively steady since the 2017-18 school year.

During a recorded meeting of the Commission in March 2022, chairman Balko presented seclusion and restraint data for the school years 2017-18 through 2020-21.

“When you guys get that information, is there anything that you guys do once you look at the data,” Dodson asked.

“Not really,” responded a DOE staff member. “Because I don’t have the time to actually sift through and go through that.”

Nicole Hicks, a member of the commission and IN*SOURCE employee — an advocacy organization for families of children with disabilities that is affiliated with the state — also expressed concern about the data.

“I’m more worried about the zeros. Because I know there’s an uptick [in seclusion and restraint incidents]. And I know, I mean, I’m hearing, you know, on the ground, and there’s a lot of challenges going on,” Hicks said.

Hicks said she was concerned that schools might not understand what constitutes a seclusion or restraint and that’s why the numbers are so low.

The meeting concluded with no clear resolution.

Dodson said in an interview that it’s been difficult to keep the DOE focused on seclusion and restraint.

“And it’s concerning, specifically when we know that the data that is being reported is incorrect,” she said. “And schools are not following the law the way that they need to be following the law.”

Molinari, a spokesperson for the DOE, wrote in a statement that the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act gives the department the authority to investigate seclusion and restraint incidents, but only if a parent files a special education complaint that alleges that the student was denied a free, appropriate public education.

Parents and guardians can submit general complaints to the department by filling out a form titled “Reports Related to the Use of Seclusion & Restraint.”

But Molinari wrote that the DOE has no power to investigate general complaints from parents regarding seclusion and restraint, because they fall outside the department’s authority.

A seclusion room at an Indiana elementary school. Submitted photo.

Solutions to a national problem

Underreporting and misreporting of seclusion and restraint data is not unique to Indiana. Federal government watchdogs, advocates for children with disabilities and researchers agree it’s a nationwide problem. But there are solutions.

Schools are required to report incidents of seclusion and restraint as part of the Civil Rights Data Collection, a program administered by the Office for Civil Rights within the U.S. Department of Education.

But an analysis of the 2015-16 CRDC seclusion and restraint data concluded that “it is impossible to accurately determine the frequency and prevalence of restraint and seclusion among K-12 public school students” due to “significant data quality problems,” according to a 2020 report from the Government Accountability Office.

That’s a problem, because when federal data is misreported, it’s not a reliable source of information to inform policy decisions or determine if use of these measures is discriminatory, excessive or both, according to the GAO report.

School districts were entering zero incidents of seclusion and restraint “when they didn’t actually have zero incidents,” said Jackie Nowicki, director of K-12 education at the GAO. Nationwide, 70 percent of school districts reported having zero incidents of seclusion and restraint during that academic year.

The GAO found that the CRDC did not have data quality controls to flag potentially erroneous zeros; the office had a rule that required verification of zeros, but it only applied to 30 of the nation’s roughly 17,000 school districts.

The GAO issued six recommendations to the OCR to fix the data reporting issues. Five of these recommendations have been implemented by the U.S. Department of Education, while one — identifying factors that cause underreporting and misreporting of the data — is still in process.

“[The Office for Civil Rights] really had no clear understanding of why so many school districts were under-reporting and misreporting. And so we felt, you know, that without understanding that more fully, that they really wouldn’t be able to help districts improve the accuracy and utility of their data,” Nowicki said.

As a federal watchdog agency that provides nonpartisan, fact-based information to Congress, the GAO does not have the power to make recommendations to state agencies. But many of the recommendations included in their report could be used to improve data collection at the state level as well.

The Indiana DOE did not respond to questions about whether the department will make changes to its seclusion and restraint data collection practices.

Parents forced to hold schools accountable

In Indiana, Tom Blessing said it’s up to parents to try to hold schools accountable for violations of restraint and seclusion policies, because the state won’t.

Blessing, a special education attorney for 13 years, said school districts routinely violate their own seclusion and restraint plans.

“It has been happening the whole time I’ve practiced special education law,” Blessing said. “And it continues to this day.”

Blessing is representing Swinehart in a lawsuit against Warsaw Community Schools. The suit alleges that school employees discriminated against her son on the basis of his disability, and that they used the seclusion room as a form of punishment or as a convenient way to address his disruptive behavior.

Warsaw Community Schools issued a statement to WFYI that said the district’s policies governing the use of restraint and seclusion are designed to protect students from harm, and the district is confident it “followed the proper laws and protocols in handling this disruption.” WSC addressed a specific incident in their statement, but provided few details.

“Due to the privacy interest of all students impacted, WCS cannot comment further on the pending litigation except to commit that it will continue to ensure all students will be provided with a safe and educational environment,” the statement reads.

Blessing said schools will often use euphemisms for seclusion rooms, like “the break room, the calming area, the time out room.”

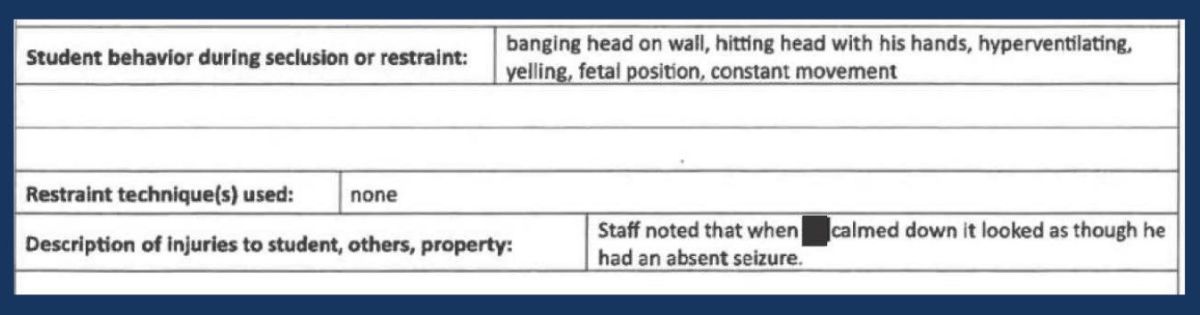

This is a copy of a seclusion report for Swinehart’s son from March 2022.

School records indicate that Claypool staff — the elementary school where Swinehart’s son is enrolled — called it “the calming room.” But school records indicate that her son would sometimes hyperventilate, bang his head against the wall, hit himself, scream, and curl up in a fetal position while in seclusion.

Blessing said often the only way for parents to get these practices to stop is to sue.

He said it’s up to parents to demand documentation and maintain communication with teachers.

“These parents are forced to become sort of a private attorney general, to enforce the laws which the state of Indiana should be enforcing,” Blessing said.

Swinehart said she’s made a point to spread awareness about the issue. She shares her family’s story with parents of children with disabilities, and recommends they ask school employees about behavior interventions and about seclusion and restraint practices.

But Swinehart is frustrated the state hasn’t done more to hold schools accountable.

“That’s upsetting, extremely upsetting,” Swinehart said. “What good is this policy if no one’s following it, and if there is no accountability?”

Eric Weddle edited this story for broadcast and digital.

Contact WFYI education reporter Lee V. Gaines at lgaines@wfyi.org. Follow on Twitter: @LeeVGaines.