Indiana parents are kept in the dark as schools isolate and restrain kids thousands of times

This is the second part of an investigation into seclusion and restraint in Indiana schools. You can see the first part here.

The seclusions began when Luvmi Webber’s son was just 6-and-half years old. When she thinks about what he experienced confined by himself to a small room in his Indianapolis elementary school, she begins to cry.

“It bothers me that they would do that to someone so young,” Webber said. “He didn’t fully understand why he’s getting locked in a room. Most kids at 5, 6, 7 years old would not.”

Webber’s son struggled to behave in the first grade: He couldn’t sit still; he’d get up out of his seat; sometimes he’d try to run out of the classroom; and once he threw his shoe at the ceiling.

To control his behavior, staff would put their hands on her son to restrict his movement — known as a physical restraint — or they’d take him to a seclusion room. Indiana defines seclusion as the confinement of a student alone in a room or area from which they’re prevented from leaving.

The room, as Webber described, is a 10-by-10-foot space with no windows to the outside, just a small aperture on the door. Her son was left alone in the room until a school employee decided he was calm enough to come out.

In the middle of his first grade year, school staff told Webber that her son had a behavioral disability. His diagnosis is listed as “other health impairment” — a catchall phrase for a multitude of disabilities — on his individualized education program.

His district — Perry Township Schools — placed him at Rise Learning Center, a school that exclusively serves students with disabilities in and around the southern part of Indianapolis. Webber’s son attended Rise for roughly four years.

Then in the fourth grade, the 10-year-old boy was secluded on 23 occasions and restrained five times, according to information provided by Rise.

“I’ve never locked him in his room,” Webber said. “So it really pains me that they used that method so many times.”

In a recent interview, Webber’s son, now 11, said staff at Rise put him in seclusion for a variety of reasons including: “not picking up my pencil and writing, or something they tell me to do and say no, running out the room, or when I’m asked to do something I don’t like and I say no.”

WFYI is not using Webber’s son’s name because he is a minor.

He said school employees would sometimes pick him up by his arms and legs and carry him to a seclusion room. He said they’d put him there multiple times a day if he couldn’t control his behavior.

“It felt like I was kind of in a prison cell,” Webber’s son said. “And usually I just walk in circles, having my finger against the wall, just dragging it against the wall.”

Students in Indiana are secluded and restrained thousands of times each year, according to data provided by the Indiana Department of Education. But a lack of transparency — in both general education and special education environments — means parents aren’t aware of the extent to which these interventions are used in schools.

And interviews with parents across the state indicate they aren’t always notified by schools that their children have been secluded or restrained, and if they are notified, the information they’re provided isn’t always detailed.

An investigation by WFYI has found schools are not always accurately reporting restraint and seclusion numbers to the state, nor are they always following their own policies when it comes to documentation and the reasons they use to justify restraint and seclusion of students.

In 2013, Indiana approved a law that was intended to regulate and curb the use of restraint and seclusion in schools. But a decade later, families still don’t know how often these practices are being used in schools.

A lack of state oversight means there is no accountability for schools that fail to accurately report incident data or fail to follow state rules governing the use of these measures. And while school-based metrics like graduation rates, test scores and other data points are available online, parents like Webber are left in the dark about how often children in schools are forced into isolation or being forcibly held by staff.

Students with disabilities are disproportionately subjected to restraint and seclusion in schools. And some students who have needs that cannot be met in a general education environment are sent to schools and programs that exclusively serve students with disabilities. A WFYI investigation found that students in these programs are frequently secluded and restrained and that those incidents are hidden from public view.

Hidden data

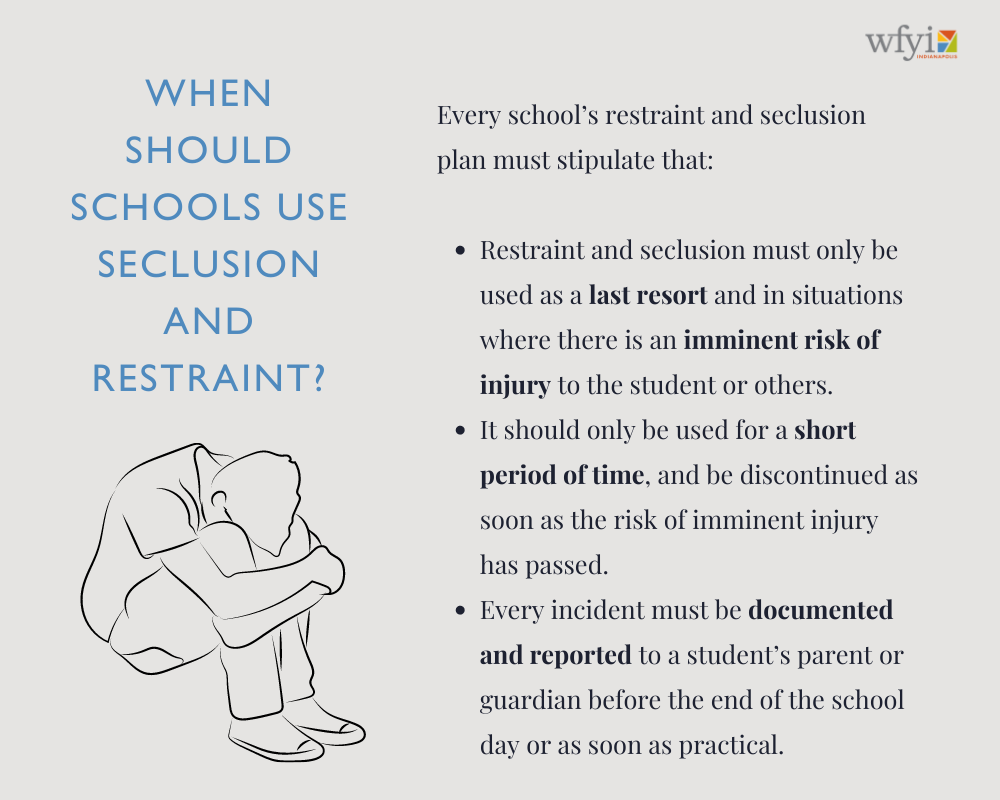

School districts are required by state law to adopt plans that govern the use of these interventions. And each plan must stipulate that seclusion and restraint should only be used as a last resort, when other deescalation measures have failed, and in situations in which there is an imminent risk of injury to the student or others.

State rules also require schools to report incidents of restraint and seclusion to the DOE as part of their annual performance reports. But these reports are hard to find on the DOE website, and there is no public database that allows parents to search for this information by school or district. Indiana GPS — the state’s new portal for student metrics — also does not include this data.

Nationally, students with disabilities are disproportionately subjected to restraint and seclusion in schools. The practice has resulted in injuries and, rarely, deaths of students.

Students with disabilities who have extensive support needs are sometimes placed in segregated schools or programs. These schools are operated by agencies — commonly referred to as cooperatives or interlocals — that serve students from multiple districts.

An investigation by WFYI identified hundreds of incidents of restraint and seclusion that were never reported to the state. WFYI submitted records requests and received restraint and seclusion data from three special education programs.

Kim Preston, a spokesperson for the DOE, said special education schools and programs that are part of cooperatives and interlocals are required to report restraint and seclusion data to the state — and that this has been a requirement since 2014.

Preston said these schools and programs had two options: Report the data directly to DOE; or report it to students’ home districts, which would then report it to the state.

But restraint and seclusion data for at least two programs was either never reported or inaccurately reported to the DOE.

SELF School

SELF School is operated by Porter County Education Services, an interlocal agency created by the seven school districts in northwestern Porter County to share special education resources. The school serves students with a range of disabilities and support needs.

PCES had never reported restraint and seclusion data specific to SELF School to the DOE until last month — following inquiries from WFYI.

SELF School recorded 1,049 seclusions and 423 restraints between the school years 2017-18 and 2021-2022, according to records obtained by WFYI in response to a public records request.

The majority of those incidents occurred during the 2017-18 and 2018-19 school years when enrollment at SELF School was at its highest during this period, with a little more than 300 full-time students.

Scott Pyle, an attorney for PCES, repeatedly asserted that PCES is not required to report this information to the state in letters and email exchanges with WFYI.

He also claimed that this data was submitted to students’ home school districts prior to the 2020-21 school year.

But that information isn’t reflected in the data submitted by Porter County school districts to the state.

During the 2018-19 school year, all seven Porter County school districts collectively reported a total of just 12 incidents of seclusion to the DOE.

That same year, SELF School recorded 495 incidents of seclusion according to data WFYI obtained — more than 41 times what was reported by all the school districts that send students to SELF.

WFYI submitted records requests to the seven Porter County school districts asking for records of restraint and seclusion data specific to SELF School. No responsive records were supplied.

Several Porter County superintendents acknowledged that they were required to submit this information on behalf of SELF School prior to the 2019-20 school year. But they also said that after that year, SELF School was required to independently report the information to the DOE.

That didn’t happen.

Kim Preston, a spokesperson for DOE, confirmed that PCES hasn’t submitted restraint and seclusion data to the department.

Pyle, an attorney for PCES, said SELF was unable to report restraint and seclusion data due to a “reporting gap” in the system that schools use to report information to the DOE.

After multiple records requests and inquiries from WFYI, Pyle wrote in a June 2 email that PCES submitted multiple years of restraint and seclusion data to the DOE on May 31.

Preston, the spokesperson for the state, wrote that the department believes “this issue will resolve itself next year” because interlocals like PCES will be required to use a new reporting system to submit this information.

New Connections

Earlywood Educational Services (EES) operates New Connections, a small program for students with extensive support needs. The program is housed in its administration building in Franklin, a town located about 20 miles south of Indianapolis.

EES is another special education agency created to share special education services between its six member school districts, including Edinburgh, Flatrock-Hawcreek, Franklin, Greenwood, Nineveh-Hensley-Jackson, and Southwestern Shelby Consolidated schools. Earlier this year, the governing board for EES voted to dissolve the special cooperative, but it will continue to operate through June next year.

The New Connections program enrolled a total of about 35 students over the last four school years.

Under their seclusion and restraint plan, Earlywood Educational Services is supposed to establish a committee to conduct an annual review of all restraint and seclusion data. But when WFYI requested this data, Angie Balsley, executive director of Earlywood Educational Services said data was maintained by students’ home districts and those districts were delegated to review it.

But a WFYI analysis of the data shows that this information wasn’t always accurately reported by students’ home schools.

An EES staff member compiled the program’s restraint and seclusion numbers based on reports they still had.

New Connections recorded 385 seclusion incidents and 624 restraint incidents for the school years 2017-18 through 2021-22, according to records provided by EES.

They couldn’t guarantee that this data captures all restraint and seclusion incidents.

For example, the Nineveh-Hensley-Jackson school corporation reported fewer incidents for its entire school district than the number of restraints and seclusions of NHJ students documented by New Connections.

Similar seclusion and restraint data discrepancies were found for Greenwood, Flat-Rock Hawcreek, Franklin and Edinburgh school corporations.

Balsley confirmed these discrepancies. In response to WFYI’s requests, she wrote in an email that she had discovered “a gap in the data reporting procedure. It has now been corrected.”

Balsley also confirmed, under the current data reporting structure, there is no way for either parents, the wider public or the DOE to know how many incidents of restraint and seclusion are happening to students in the New Connections program.

A spokesperson for IDOE says beginning with the 2023-24 school year, special education cooperatives like EES and PCES will be required to directly report restraint and seclusion incidents to the state via a new data reporting system.

Rise Learning Center, located on the southside of Indianapolis, serves students with disabilities from multiple school districts.(Dylan Peers McCoy/WFYI)

Rise Learning Center

Luvmi Webber has also struggled to find out how often and for what reasons her son was secluded and restrained at Rise Learning Center.

The Southside Services Cooperative of Marion County (SSSMC) — which operates the Rise Learning Center — is another special education cooperative. It was created to share special education resources between Perry Township, Decatur Township, and Beech Grove schools.

When asked for restraint and seclusion data, Rise provided two years worth of information that included the names of students and other personally identifiable information to WFYI.

WFYI did not request personally identifiable student information.

Providing a journalist with the names of students who were restrained and secluded at school is prohibited under the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act.

Scott Carson, executive director of Rise Learning Center, wrote via email that the disclosure of personal student information was “a good faith error.”

Webber’s son was among the names of students provided by Rise.

When contacted by WFYI, Webber was surprised by the number of times her son was restrained and secluded last year. Only one other student — another child in the school’s behavioral program — was secluded and restrained more than him.

“Once he started going to Rise, they stopped really calling and letting me know he was going into seclusion or having a behavioral issue really at all,” Webber said. “They just would write it down on a sheet and give it to me in his book bag.”

Webber said she would have preferred for the school to call her to let her know that her son was struggling to control his behavior.

“Because I feel like it escalated the situation instead of calming the situation down by trying to put your hands on him and put him in the [seclusion] room,” she said.

Carson wrote via email that parents can choose how they’re notified about restraints and seclusions, including via “phone calls, emails, daily behavior sheet or copies of the seclusion form.” He wrote that Webber was “informed in person at pick up, on the daily behavior sheet, and occasionally via email; these contacts are documented on the restraint and seclusion form.”

Rise recorded 919 incidents of seclusion and 413 incidents of restraint for the school years 2018-19 through 2021-22, according to records provided by Rise to WFYI.

During those school years, enrollment at Rise ranged from about 160 to 200 students.

Rise reported seclusion and restraint data to the DOE for the last three school years under Southside Services Cooperative of Marion County. That information is not posted on the state website, and Rise reported zero restraints and seclusions to the state during the 2018-19 school year, according to data provided to WFYI by the DOE.

Carson said the DOE requested they report their data directly to the department for the 2019-20 school year, which is what they’ve continued to do in subsequent school years. While this data is included in what the DOE provided WFYI, it cannot be found online.

Carson said that prior to the 2019-20 school year, they reported their seclusion and restraint data to students’ home school districts.

But that doesn’t appear to be reflected in what was reported by school corporations who sent students to Rise.

For example, in data it shared with WFYI, Rise documented 86 seclusions involving students from Perry Township schools and 25 involving students from Beech Grove schools; Rise also documented 66 restraints involving students from Perry and 18 involving students from Beech Grove during the 2018-19 school year.

But both Perry and Beech Grove school districts reported zero incidents of seclusion to the DOE that year; while Beech Grove also reported 0 restraints and Perry reported just 8 restraints.

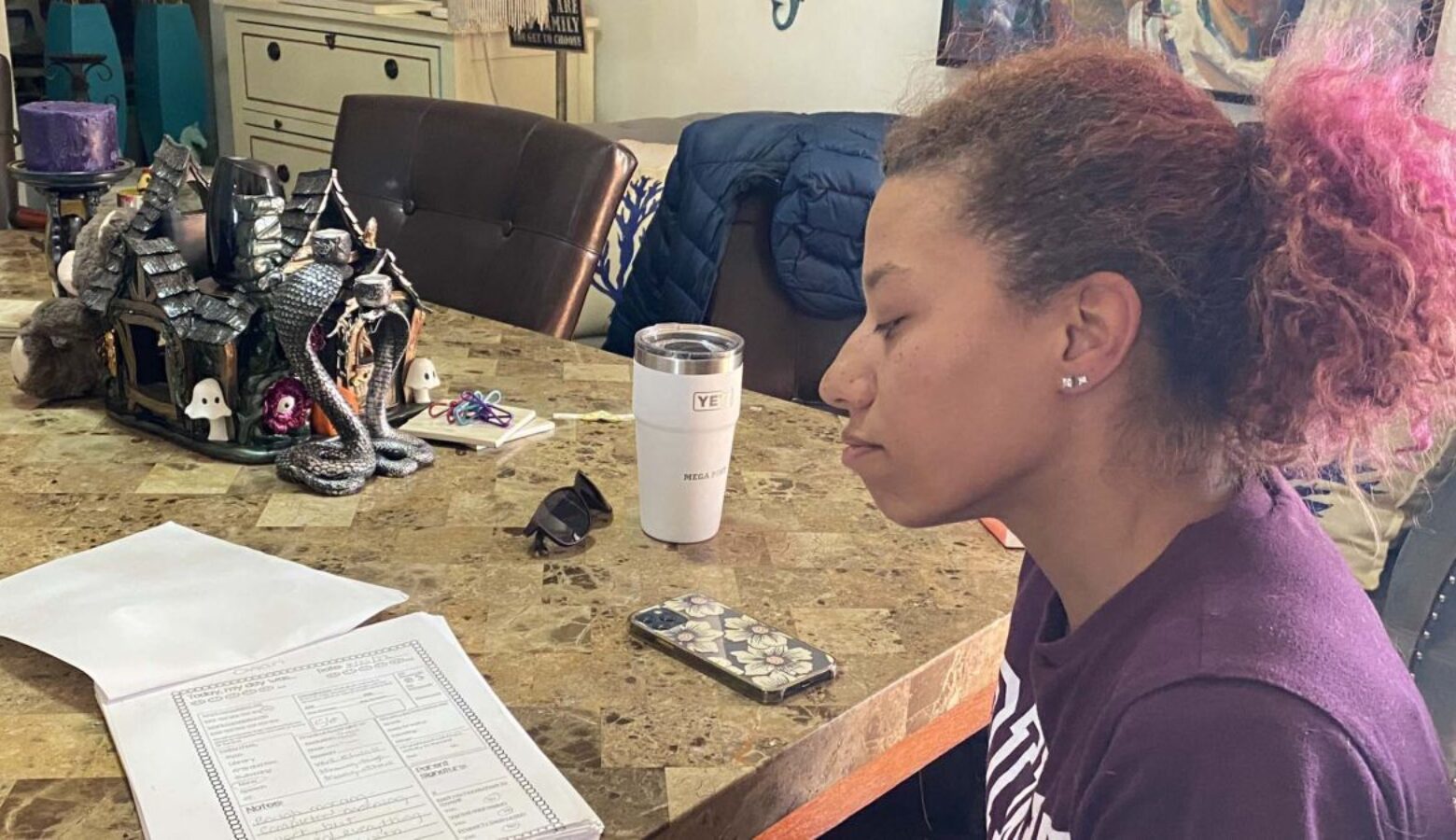

Luvmi Webber at her home in Indianapolis. She doesn’t believe her son’s former school, Rise Learning Center, always followed its restraint and seclusion plan. (Dylan Peers McCoy/WFYI)

Violations of their own policy

Webber, the Indianapolis parent, doesn’t believe her son’s former school, Rise Learning Center, followed its own seclusion and restraint plan.

The school’s restraint and seclusion plan dictates interventions should never be used “as a means of punishment or discipline, coercion or retaliation, or as a matter of convenience.”

Upon request, the school provided Webber with daily sheets that detail student behavior during the school day through the fall of last year.

They provide few details, but each sheet includes a small section where staff mark whether a student was secluded or restrained that day and some notes.

On one occasion in August of last year, they wrote that Webber’s son was secluded because he was “out of area, throwing work, climbing on desk.” Additional notes explain that her son had a physical and verbal incident with another student; he took the other student’s hat and he teased them.

Ten days later he was secluded again, this time for “work refusals, throwing things, teasing others.”

Carson, executive director of Rise Learning Center, confirmed via email that there are two instances in which the documentation does not include a behavior that would merit seclusion.

“This is an error either in implementation or documentation,” Carson wrote. He added that staff are regularly provided corrective feedback and retrained every two years. Carson wrote that all staff will be retrained when school resumes this fall.

“I do think they’re using it as punishment,” Webber said. “Because I don’t remember following every rule or doing every worksheet at school, and I was never locked in a room. I never had a teacher hold me in my chair.”

Webber is also frustrated at the lack of oversight from the state.

“How would you even know if there is someone mistreating someone or misusing the seclusion room? It’s going unnoticed for sure,” she said.

Webber’s son has since left Rise. She said she was told by Rise employees that he had made enough progress to return to his neighborhood school to finish out his fifth grade year. She’s happy he’s able to return to the general education environment. But she’s concerned how his experiences in seclusion could affect him later in life.

“I’ve worried for years, psychologically, what effect it could have,” Webber said.

WFYI reporter Dylan Peers McCoy contributed to this report.

Eric Weddle edited this story for broadcast and digital.

Contact WFYI education reporter Lee V. Gaines at [email protected]. Follow on Twitter: @LeeVGaines.