Stigma, misinformation killed bill to decriminalize test strips, advocates say

This story discusses substance use disorder and overdose. If you are looking for treatment options for a substance use disorder in Indiana, call 988 or find resources through NextLevel Recovery.

Jennings Tennery remembers going directly to her dealer’s house after leaving a detox center in central Indiana.

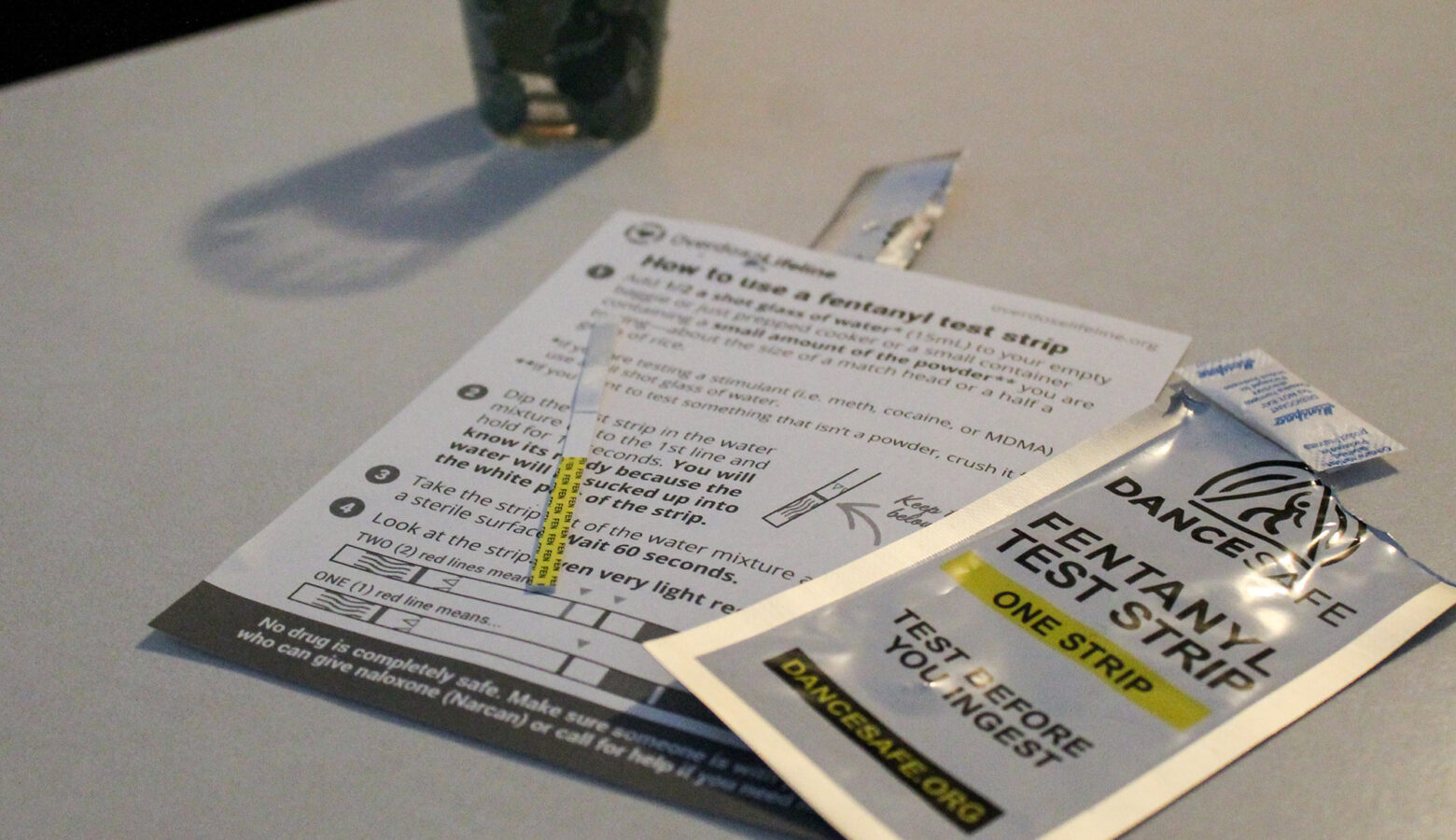

She had naloxone and a couple fentanyl test strips that the staff had given her. Tennery usually used alone, but that day the test strips gave her a moment to pause.

“When the test came back positive for fentanyl, I decided not to use alone that day,” Tennery said. “And I ended up overdosing.”

The people she was with administered naloxone, which rapidly reverses opioid overdoses. Tennery said she wouldn’t have had the chance to find recovery without the test strip giving her the control to make a different decision.

“You can’t find recovery, you can’t be sober if you’re dead,” Tennery said.

Tennery has maintained recovery since that day and now works as the grants and finance manager with an advocacy organization called Overdose Lifeline, which distributed more than 170,000 test strips last year alone.

Advocates, like Tennery, said test strips are a safe, simple, effective harm reduction tool.

However, the legality of the tool in Indiana is a bit of a gray area.

The legislative stigma

Indiana law classifies tools that test the “strength, effectiveness, or purity of a controlled substance” as paraphernalia. Test strips only identify the presence of a substance.

Breanna Baldwin, director of harm reduction at Overdose Lifeline, said the tool saves lives by giving people more information.

“When I use a test strip on any type of substance, I’m not sure how much of a substance or how much fentanyl could be in that test strip,” Baldwin said. “I’m not sure of if that substance is still safe to use. I’m not sure of any of those things. All I know is fentanyl is present, which allows me to make a more educated decision.”

The language in the law is just ambiguous enough that it creates a question around them.

Tennery said there’s a human cost to the fear and confusion that section of Indiana code creates.

“People are dying because they don’t feel comfortable having the fentanyl test strips or don’t know that they can still get them or have them,” Tennery said.

Some lawmakers think Indiana should explicitly decriminalize test strips.

Rep. Victoria Garcia Wilburn (D-Fishers) proposed legislation in the 2024 legislative session to do that. She said HB 1053 would have clarified state law.

“In all accords, they are technically legal,” Garcia Wilburn said. “But if they are interpreted too stringently, some might venture to say they’re still illegal.”

In addition to her role as a state representative, Garcia Wilburn is also a community-engaged researcher with Indiana University’s School of Health and Human Sciences. Her research has involved working with community organizations that address substance use disorder.

Her experience outside of the Statehouse led to her identifying test strips as a vital tool to addressing substance use disorders “along a continuum of harm reduction.”

Garcia Wilburn worked with advocates, prosecutors, law enforcement and other lawmakers to determine what the best course of action was. Her legislation would have removed the provision that classified tools that test substances as paraphernalia. She said this approach has been used in other states, like Mississippi and Florida.

In fact, Indiana is in the minority of states when it comes to decriminalizing tools like test strips.

“This is a decision to choose life,” Garcia Wilburn said. “It should have been fully embraced in Indiana as well.”

The legislation had bipartisan support, passing the House with only one vote in opposition. However, it was one of only two bills that didn’t receive a hearing in the Senate Corrections and Criminal Law Committee.

Garcia Wilburn said the bill likely died due to stigma around substance use and misinformation on what harm reduction does.

“There are some people in this General Assembly that still view substance use disorder as a moral failure,” Garcia Wilburn said.

She said harm reduction tools, like test strips, address substance use through a public health lens. The idea is to equip people with tools and resources that could save their lives — giving them another opportunity to seek treatment.

Baldwin, with Overdose Lifeline, said harm reduction is becoming a larger topic in the state — especially with the impact that substance use has had in Indiana.

In 2022, Indiana was among the highest overdose mortality rates in the country.

“Opioid overdoses are the leading cause of death between anybody ages 18 to 45 across the nation, which means that we obviously are doing something wrong,” Baldwin said. “Harm reduction has become such an important aspect, and I think our local and state legislators are starting to realize that.”

A murky legal environment

Zach Stock, legislative counsel for the Indiana Public Defender Council, said some people view the decriminalization of harm reduction tools as an endorsement of substance use. But he said this legislation could have been a crucial step to show how a “modest, incremental change” can make a huge impact.

“It doesn’t mean that full scale legalization is right around the corner,” Stock said.

Currently, the legal environment around test strips isn’t stable, with varying attitudes about prosecuting paraphernalia around the state.

“You may have elected prosecutors who have chosen to say, ‘Well, I’m not going to prosecute people engaged in genuine harm reduction,’ but you have no guarantee of that,” Stock said. “And a reform-minded prosecutor can be replaced by a more punitive-minded prosecutor in the next election.”

Stock said it can be used to justify “searches and seizures that reveal larger criminality.”

“Depending on how it’s enforced, this is not universal, it can be a tool — is often a tool — to the search of a car or the search of a person, which leads to just a general sort of invasion of privacy,” Stock said.

The Indiana Constitution says the state’s penal code should be founded on the “principles of reformation” rather than “vindictive justice.” Stock said there’s decades worth of historical context that shows punishing substance use “out of existence” doesn’t work, but that doesn’t mean the criminal and legal system can’t play a role in addressing substance use.

“If that criminal justice system involvement is not leveraged for treatment, education, job skills training or the like, then it’s just a setback,” Stock said.

Stock said that setback is the last thing people need when they’re navigating substance use issues. He said decriminalizing test strips fits into the state’s responsibility to focus on reformation and it gives people access to a tool that can be used for “self-preservation.”

The ambiguous language around test strips not only impacts people who use them, but Stock said it can also create that sense of fear and confusion for first responders and advocates distributing or supplying test strips.

“They may just do it whether the law says they shouldn’t be doing it or not,” Stock said. “They’re kind of brave people in that regard, but I think there’s going to be other people who are more hesitant now that they know. They’re going to say, ‘Boy, I don’t know if I should do this.’”

Stock said removing the language gives people the flexibility and security to use and supply such an important tool.

Join the conversation and sign up for the Indiana Two-Way. Text “Indiana” to 765-275-1120. Your comments and questions in response to our weekly text help us find the answers you need on statewide issues and the election, including our project Civically, Indiana.

With the current language, the uncertainty on legality also prevents Indiana from having access to additional funding, according to Garcia Wilburn.

“Uniformity allows for better planning and allows for more coalition building,” Garcia Wilburn said. “It allows us to have more federal funding, through the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Association. There’s lots of ways that we can help support Hoosiers. And right now we just don’t have that full access to support.”

She said communities want to see people get the support they need and people should be treated the same no matter where they are in the state.

The future Statehouse fight

Garcia Wilburn said this is the first time someone has proposed this legislation, and she’s committed to bringing it back next legislative session.

That’s fairly common: bills often don’t make it through the General Assembly at first. Depending on the complexity of the measure, it can take several years for a bill to become a law.

Garcia Wilburn said she thinks it’s time for the state to see progress.

“We don’t have the mental and behavioral health infrastructure in our state yet to be able to service everybody with substance use disorder,” Garcia Wilburn said. “Until that day comes, we want people to continue to be alive to seek treatment.”

She said she hopes lawmakers use the interim to educate themselves and hear from constituents.

For now, the ambiguous language is still in state law.

Despite that, Overdose Lifeline will continue to provide the test strips, according to Baldwin.

“We’re able to provide this tool regardless of the legal gray area, because we know through interpretation of the law that they are legal,” Baldwin said. “We are not afraid of providing this to individuals that need it.”

Tennery said advocates are more interested in saving lives than “getting held up on those gray areas.”

“We’re worth saving,” Tennery said. “It is a risk, but it’s a risk worth having.”

Abigail is our health reporter. Contact them at [email protected].