Death row inmate Joseph Corcoran executed for quadruple murder

The Capital Chronicle was the only media present for the execution inside the Indiana State Prison.

Convicted murderer Joseph Corcoran was pronounced dead by lethal injection at 12:44 a.m. Wednesday morning, marking the first Indiana execution since 2009.

Corcoran and his legal team allowed a reporter from the Indiana Capital Chronicle to witness the execution at the Indiana State Prison. No other media were permitted to be present.

It’s not clear when exactly the execution drug, pentobarbital, was administered into Corcoran’s left arm, via an IV line that protruded from the execution chamber’s wall.

Department of Correction officials said in a statement that “the execution process started shortly after” 12 a.m. Central Time. Entry into the witness room was not allowed until 12:32 a.m.

Four people were present in the witness area meant specifically for Corcoran’s family and friends: a Capital Chronicle reporter; Corcoran’s wife, Tahina, and her son; and federal defense attorney Larry Komp.

It’s not clear who was present in a different witness area for victims’ families because the list is confidential and the two witness parties were kept separate by DOC staff throughout the entire process.

Blinds for a one-way window with limited visibility into the execution chamber were raised at 12:34 a.m.

Corcoran appeared awake with his eyes blinking, but otherwise still and silent, at that time. After a brief movement of his left hand and fingers at about 12:37 a.m., Corcoran did not move again. Blinds to the witness room were closed by the prison warden at 12:40 a.m.

Corcoran, who had been on death row since 1999, was 22 when he killed his brother, James Corcoran, 30; Robert Scott Turner, 32; Douglas A. Stillwell, 30; and Timothy G. Bricker, 30, on July 26, 1997. He committed the murders at the home he shared with his brother and a sister.

The condemned man had long resisted opportunities to appeal his case that could potentially overturn his death sentence. His death warrant was carried out after several weeks and months of last-minute attempts by his lawyers to pause the execution and allow for his mental competency to be reassessed.

Corcoran’s mental health had been a part of the decades-old case since its inception, with state and federal public defenders saying he suffered from paranoid schizophrenia that caused him to experience “persistent hallucinations and delusions.”

The Indiana Supreme Court upheld the death sentence earlier this month, just as multiple state and federal courts had done. Appeals for post-conviction relief at the federal level were unsuccessful, too. Late Tuesday night, the U.S. Supreme Court also denied a last-ditch request for relief filed by Komp.

That meant final intervention was left to Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb, who ultimately rejected calls for a pardon.

“Joseph Corcoran’s case has been reviewed repeatedly over the last 25 years – including 7 times by the Indiana Supreme Court and 3 times by the U.S. Supreme Court, the most recent of which was tonight,” Holcomb said in a statement shortly after 1 a.m. Wednesday. “His sentence has never been overturned and was carried out as ordered by the court.”

Corcoran’s final moments

The execution was the first in which Indiana used the one-drug method. Previously, the state used a lethal combination of three substances to induce death.

While separate from state death warrants, 16 other executions have taken place at the federal prison in Terre Haute since 2001, some of which were carried out using pentobarbital.

Witnesses were unable to hear voices inside the execution chamber; DOC officials said Corcoran’s last words were, “Not really. Let’s get this over with.” That came after requesting Ben and Jerry’s ice cream as his last meal.

Rev. David Leitzel, Corcoran’s Wesleyan minister, was allowed within the execution chamber as Corcoran died.

Leitzel told the Capital Chronicle that he and Corcoran “had the better part of an hour to talk together” in a holding cell before the execution.

“We had serious conversation. We had prayer together. We talked and laughed, we reminisced, we had stories, we had memories, we talked about spiritual things — it was kind of a standard time of talking with him,” said Leitzel, who’d known Corcoran since the early 1990s. “When going into it, he actually was talking more about the other guys on death row, and how it was going to impact them. He wasn’t talking about his own feelings and fears. He had talked to me about that at one point, but his greatest fear was that it would not be peaceful. From my perspective, it was very, very peaceful.”

Once in the chamber, the minister said he offered his hand to Corcoran.

“When I got in there, they said that I could hold his hand. But Joe said, ‘Oh, don’t hold my hands.’ He just said, ‘Pray for me.’ And so I just prayed,” the minister continued. “He definitely was good to go … and I don’t say that lightly. The only thing Joe’s ever asked for prayer-wise, regarding the executions, was about some of the stuff he’d heard … that he didn’t know what would happen. And so I just say, ‘Thank you, God,’ for that, because from my perspective, it was very peaceful.”

DOC originally denied a request from Corcoran’s attorneys to allow Leitzel to be present in the execution chamber with a Bible, and to be permitted to pray with Corcoran. After the inmate’s lawyers filed a federal lawsuit, the agency agreed to let a “spiritual advisor” have limited physical contact with Corcoran during the execution.

Ron Neal, the prison warden, was also present in the chamber, along with an unidentified woman. Although multiple people are involved in the Indiana execution process, their identities have historically been kept confidential, as instructed under the law.

Neal was responsible for selecting an executioner, who was not visible from the witness room and remains anonymous. State law does not stipulate who can administer life-ending drugs, but the act is typically carried out by a physician.

The Indiana Department of Correction has not answered the Capital Chronicle’s requests for information about who has been selected for Corcoran’s execution, nor has the agency indicated how much the state paid for the execution drug.

State officials defend execution

Indiana Attorney General Todd Rokita defended the execution shortly after it was carried out.

“Early this morning, Indiana conducted its first execution since 2009. Joseph Corcoran’s case worked its way through our judicial system and today he finally paid his debt to society as justice was provided to his victims,” Rokita said in a statement. “A jury recommended and a judge imposed a sentence of death for the senseless murders of four people. My office fought to defend that sentence and state law every step of the way, and the Indiana Department of Correction carried it out professionally.”

Allen Superior Court Judge Frances C. Gull, who presided over Corcoran’s 1999 trial and ultimately sentenced him to death, additionally weighed in.

“State of Indiana vs. Joseph E. Corcoran has come to the end prescribed by Indiana law, found appropriate by a jury of the defendant’s peers and upheld repeatedly through the appellate process,” Gull said in a statement following the execution. “My only thoughts today are with the families of those he was found guilty of murdering. I hope they find some measure of peace knowing that his sentence has been carried out.”

Tahina said she and her husband discussed faith and memories — including from their time in high school together — on Tuesday, before the execution. Opposed to the execution, she said her husband was “very mentally ill” and was “in shock” during their last visit. Tahina did not speak immediately following the execution.

His body will go to the county coroner first and then cremated with his ashes turned over to his wife.

Three masked officers presented news reporters with a written DOC statement outside the state prison shortly before 5 p.m., but they did not speak or answer questions.

A second DOC statement was issued at 12:59 a.m., in the minutes following the conclusion of Corcoran’s execution, indicating his time of death and last words.

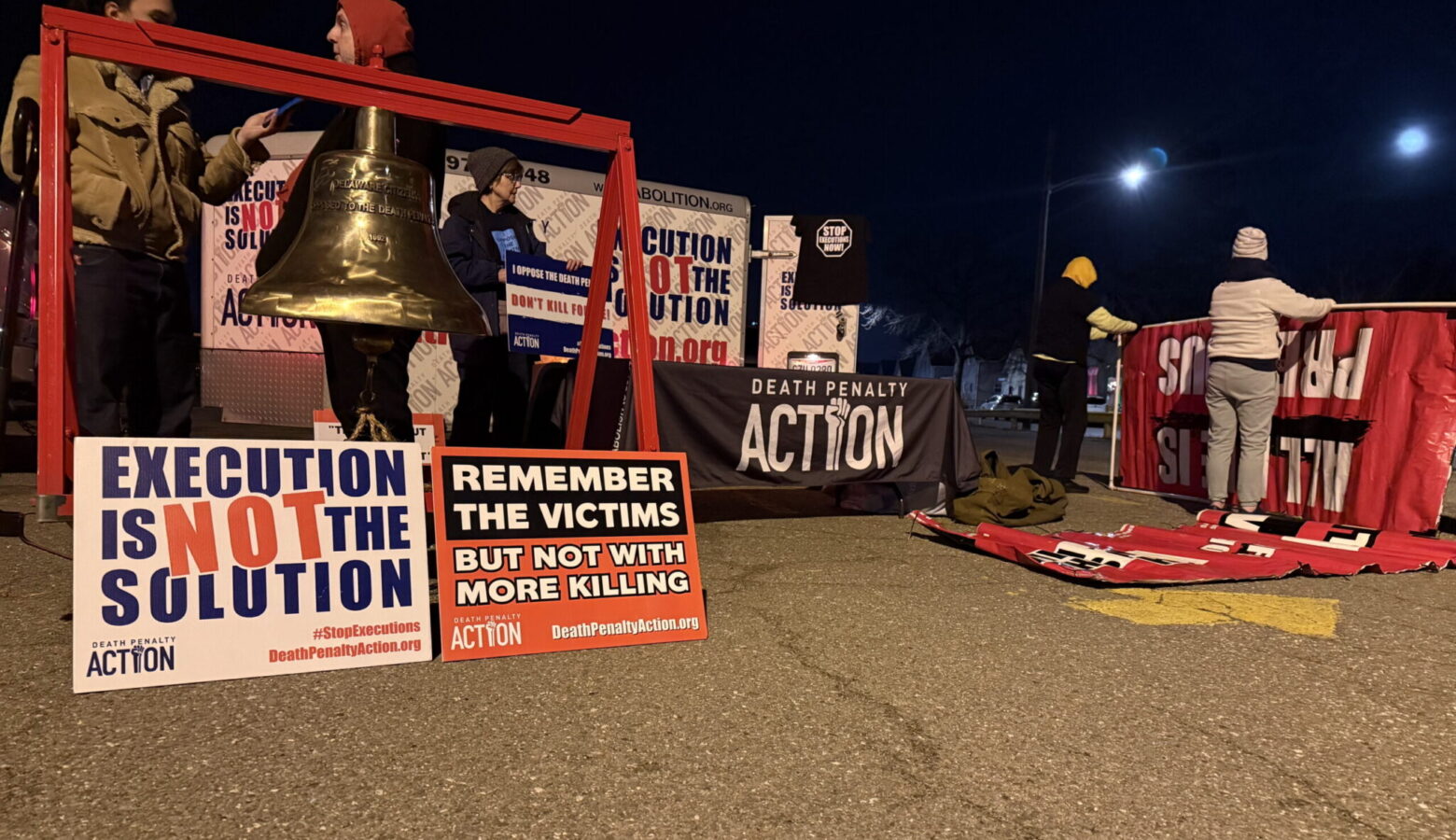

Outside the prison Tuesday night, roughly three dozen protesters gathered to pray and call on state officials to stop the execution.

That included Bishop Robert McClory, of the Catholic Diocese of Gary, who said the goal was “not to give grand speeches — we’re just here to pray.”

Death Penalty Action, a nonprofit that advocates against executions, had in tow its “Delaware Bell,” which the group has rung outside more than a dozen other executions.

Echoes from the bell could be heard shortly after midnight from inside the Indiana State Prison offices — where witnesses waited before being transported by a DOC van to the execution chamber.

“There is no reason for Indiana to resume executions, and especially not with a man who is severely mentally ill,” said Abraham Bonowitz, Death Penalty Action’s executive director. “Indiana has been safe from people who have committed awful crimes while holding them accountable without executions for nearly 15 years.”

There were separate pleas to spare Corcoran’s life before the execution, as well.

Last week, a delegation of faith leaders opposed to the death penalty descended upon the Indiana capitol to deliver a letter to Holcomb, imploring him to stop Corcoran’s execution and “refrain from restarting executions in Indiana” altogether. Corcoran’s lawyers said numerous other similar letters were forwarded to the governor’s office.

Before that, Fort Wayne Republican Rep. Bob Morris called on Holcomb to block Corcoran’s execution — and death sentences for Indiana’s seven other death row inmates. The lawmaker additionally said he plans to introduce a bill in the 2025 legislative session to end capital punishment in Indiana.

Last-minute pleas denied

Corcoran’s defense lawyers have long maintained that “severe mental illness” caused their client to make decisions that weren’t in his best interest and instead ensured his spot on death row.

Corcoran’s mental illness was documented in court filings as early as age 17, when he underwent a psychological evaluation following the deaths of his parents. He was charged with killing them when he was a juvenile but was acquitted.

Doctors who evaluated Corcoran over the last three decades have reached multiple diagnoses, including depression, paranoid schizophrenia and schizoid personality disorder.

State attorneys originally offered Corcoran a life sentence if he would accept a plea or waive jury. He refused, however, saying he would only agree to the terms if the state “would sever his vocal cords first because his involuntary speech allowed others to know his innermost thoughts,” according to court documents.

Later, at his sentencing, Corcoran stated that he wanted to waive all his appeals. And in the early 2000s, when the time was still ripe for Corcoran to initiate post-conviction review, he refused to sign the post-conviction petition.

In recent months, Corcoran was unwilling to sign the necessary paperwork to initiate a clemency review or other avenues that could have resulted in his removal from death row.

The inmate’s attorneys pointed to delusions he had about ultrasound machines controlling him and his thoughts. But attorneys for the state maintained he was competent to be put to death.

They asserted that Corcoran wanted to be executed and had “a rational understanding of the reason for his execution.” The attorney general additionally pointed to a 2006 letter and statements in years past in which Corcoran “admitted he fabricated this delusion.”

Earlier this month, the Indiana Supreme Court sided with the state in a 3-2 decision, denying requests by Corcoran’s lawyers to delay his impending execution date and allow for his case to be reviewed or his sentence overturned. A different order issued by the court last week again denied a stay.

Corcoran’s legal team asked a federal judge to step in and pause the execution to allow for a hearing and review of their claims that putting the inmate to death is unconstitutional. But in his Friday order, Judge Jon DeGuilio, of the U.S. District Court in Indiana’s Northern District, said claims that Corcoran is incompetent to be executed are “procedurally defaulted and without merit.”

Komp argued that Corcoran’s mental illness had long distorted his reality and made him unable to understand the severity of his punishment. He said his client “lacks any rational understanding of his impending execution — he simply wants to expedite the ending of the torture that is not real.”

That’s despite a November letter Corcoran sent to the high court, in which he said he has “no desire nor wish[es] to engage in further appeals or litigation whatsoever.” With his “own free will” and “without coercion or promise of anything,” he asked the justices to withdraw his counsel’s motions.

A 2-1 decision by a panel of the Seventh Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals on Monday further denied a request to stay Corcoran’s execution. Concurring justices cited Corcoran’s November letter, “that articulately sets forth his desire not to pursue federal relief,” and emphasized that the inmate was found competent in 2004, “and he has not ever been adjudicated incompetent.”

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett issued a final blow shortly after 9 p.m. Tuesday, denying a petition to stay the execution. Komp argued in the high court filing that Corcoran’s lawyers were not given a fair opportunity to respond to his November letter, and stressed that his client deserved a new, “proper competency test” before being put to death.

Case background

Corcoran told police at the time of the killings that the four men had been talking about him. He first placed his 7-year-old niece in an upstairs bedroom to protect her from the gunfire before killing the four men.

He then laid down the rifle, went to a neighbor’s house, and asked them to call the police. A search of his room and attic, to which only he had access, uncovered over 30 firearms, several munitions, explosives, guerrilla tactic military issue books, and a copy of “The Turner Diaries.”

Earlier, in 1992, Jack and Kathryn Corcoran were found shot to death in their Ball Lake home. Joseph, their son, who was 16 at that time, was charged for their deaths.

In his recent letter to the state supreme court, Corcoran stated that he is “guilty of the crime I was convicted of, and accept the findings of all the appellate courts.”

Indiana Capital Chronicle reporter Casey Smith is also an instructor of journalism at Ball State University.